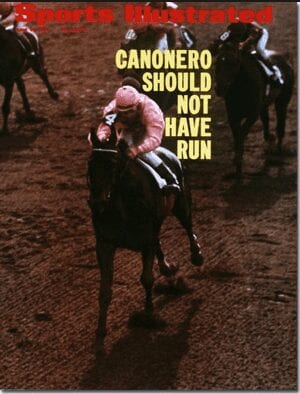

Back when I started at Sports Illustrated in 1996, the payoff for a well-done story wasn’t bonus money or a pat on the back or a special mention in a Letter from the Editor. No, it was a typed note from Peter Carry, the veteran executive editor who, quite frankly, intimidated the hell out of me.

Peter was a legendary Sports Illustrated figure who started at the magazine in 1964. He’d edited the best of the best—from Deford to Jenkins to Nack to Reilly to Smith to Rushin—and you knew (you just friggin’ knew) in order for a piece to reach the final pages, it had to pass through Peter’s red pen. Sometimes, this could be painless. A few marks here, a few comments there. Other times, however, it was brutal—you could feel great upon submission, then be told the lede sucked, the transitions were cliched and, um, what the fuck was the point?

Awful.

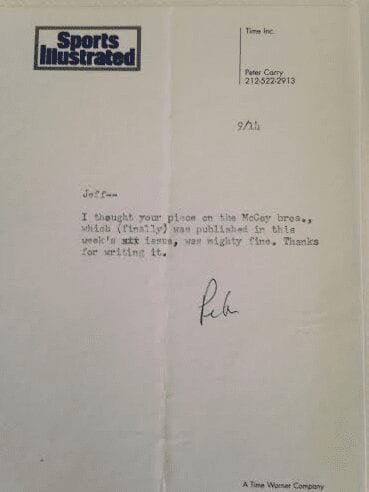

Just when you found yourself ready to seek out a gig at the Putnam County News, however, a note would arrive at your desk. One like, well, this …

And you’d fly. And soar. And jump. And leap. Those notes—rarely more than three or four sentences in length—could make a writer’s day. Week. Month. They convinced me I could succeed at Sports Illustrated; write with the best; hold my own.

And you’d fly. And soar. And jump. And leap. Those notes—rarely more than three or four sentences in length—could make a writer’s day. Week. Month. They convinced me I could succeed at Sports Illustrated; write with the best; hold my own.

In short, they meant everything. That’s why, in my old SI photo albums, I’ve kept every one Peter sent my way. They’re priceless.

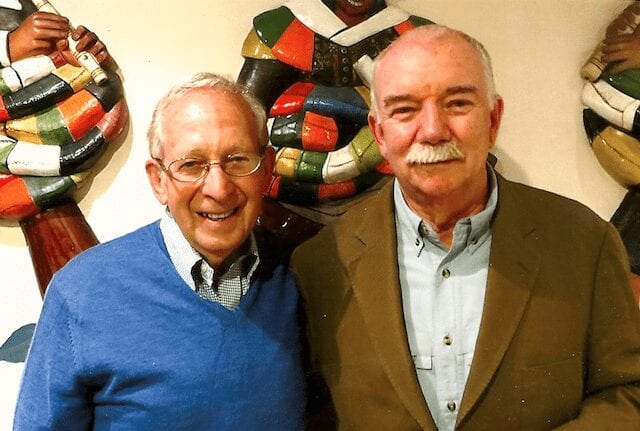

Peter left the magazine more than a decade ago, but his legacy as a fierce, hard-nosed editor remains. He also served as executive editor of Discover, a science monthly that was published by Time Inc (Both magazines won the National Magazine Award for General Excellence during his time). In retirement, he’s done a ton of charity work. He and his wife Virginia have two children and two grandchildren. They live in Harlem.

Here, Peter talks of the heyday of print journalism; of what the medium has become and what, perhaps, it can be.

Peter Carry, my editor, welcome to The Quaz …

JEFF PEARLMAN: OK, Peter, so you were at Sports Illustrated during what has to be considered the golden age. The magazine was the voice in sports journalism. Print was the medium. The best writers in the country wanted to write for SI. I’m wondering, more than a decade removed, how you feel when you see SI now. I don’t mean, “Oh, the writing sucks or is great” or anything like that. I mean—it just can’t possibly be what it was, can it?

PETER CARRY: I feel a mixture of pride and melancholy. Pride because I was involved for 35 years in putting out the superb magazine you described in your question. I’m proud that SI brought real journalism to the reporting of sports—and to related subjects like racism and the environment during various times—and I’m just as proud of the quality of the prose that appeared on its pages. I’m melancholy to a small extent that I’m no longer involved in that world—the standard retired guy’s lament—but much more because of what is happening to magazines specifically and journalism in general. SI is doing better both editorially and, I gather, financially than the majority of publications, some of which have sold out and become gossipy rags, joining the gossipy rags that were already there, and many more of which have disappeared or seem likely to do so soon.

I don’t mean to sound like the guy who bemoaned the demise of the buggy whip by decrying the advent of the automobile. The electronic means of communication we have are marvels, but we must find some way to bend their use to thoughtful and significant journalism that might be a bit slower in arriving before our eyes but will so much better nourish our brains. It’s essential to our world, our country and ourselves that we have well-informed citizens. This is a human problem, not a technical problem. I couldn’t care less if SI exists as an entity on paper 10 years from now, but I care immensely that the spirit of the magazine as you and I knew it lives on in whatever form SI and other publications with high standards might appear then. I’ll add here that I’m delighted that the current editors of the magazine have rededicated considerable space to the sort of long-form pieces that made SI’s reputation.

J.P.: I knew you as an editor at SI, but I know little of your path to the spot. So, eh, Peter, what was your path? Why journalism? What was it about the medium? And why SI?

P.C.: In the fourth grade at P.S. 13 in Valley Stream, N.Y., I was the editor of the Corona Avenue Gazette, as the mimeographed school paper was grandly called, so I guess this stuff has been in my blood pretty much all along. I remember seeing Dwight Eisenhower, then running for his first term as President, ride past the school in a motorcade and then writing a story about it. It was fun. It was exciting. It seemed important. What’s not to like? What really clinched the deal for me was when Time Inc. recruited me for its paid—I’d say well-paid, unlike those terrible unpaid summer jobs these days—internship program between my junior and senior years in college. I accepted even before I knew what publication I’d be assigned to, but because I was the sports editor of The Daily Princetonian, I wasn’t too surprised when I ended up at SI. By the end of that summer, the magazine had offered me a permanent job. I joined the staff upon graduation in June 1964 and then five months later left for three years in the U.S. Navy (the magazine graciously granted me a leave of absence, though it had no legal obligation to do so, so I didn’t have to worry about a civilian job during my 21 months in the Vietnam combat zone). I returned in time to help cover the Year of the Pitcher in 1968 and really begin my career at the magazine. I was blessed to have a large number of powerful examples to try to emulate and two terrific editors who generously mentored me, Jerry Tax and Gil Rogin.

J.P.: I’m gonna ask a weird question, and I hope I phrase it correctly. You were a power player at SI. A big editor in a big job when the magazine was all powerful. Then, one day, it ended. People always talk about the transitions athletes make when they retire, but what was it like for you? No more magazine? No more executive assistant, power lunches, name on the masthead? How did you adjust?

P.C.: Well, I didn’t tell the guy who paid me a lot of money to leave this, but I was pretty much planning to depart within two years of when I did. At that point I had been an editor at some level or another for about 30 years—that’s 1,500 late Sunday nights in the office, a goodly number of them all-nighters. I think I was pretty much gassed. It didn’t hurt that for the subsequent two winters I worked as a temporary editor at The International Herald Tribune, which you probably know is based in Paris. Along with my wife, Virginia, I got to live in the 5th Arrondissement, eat and drink in some pretty good restaurants and work on mon français. It wasn’t a bad way to wind down. I might add that SI’s Thursday-to-Monday work week and the crazy hours on the weekends were tough on the families of the staffers. Virginia handled this difficult situation with amazing aplomb, while also bringing up our two kids without a whole lot of help from yours truly.

J.P.: I’ve always hated the Swimsuit Issue. I mean, really, really hate it. I think it’s a sexist, treat-women-as-objects piece of garbage. Just being honest. Tell me why I’m wrong. Or right.

P.C.: Mr. Pearlman, you’re usually right—well, maybe—but you’ve never been righter than you are about the swimsuit issue. I thought and think it was/is boring and sexist and had/has nothing to do with the magazine’s mission. I don’t agree that it is garbage because I know the people who put it together do so with great care and creativity. That said, I must acknowledge that it was probably the swimsuit issue, which during my later years at SI represented some place between 15 percent and 20 percent of the magazine’s revenues and in that period SI had the second-highest revenues in the magazine business, that paid my kids’ tuitions at one of the most expensive damn universities in the world.

J.P.: What was your approach to editing a story? Did you look to make changes? Was the goal to make as few as possible? And did you worry about maintaining a writer’s voice? Or does that even matter?

P.C.: Well, depends on the writer, If it was one of your pieces, I’d throw the manuscript in the shit can, pull up the keyboard (né typewriter) and start pressing the keys. But if the author was Deford or Verducci or Price or Smith … Ah, just kidding, I think. The most important work was done before the story was written, even before it was even assigned. Rule 1: The best ideas come from the guys in the field (and Lord knows whatever other sources outside your office), so listen. Refine. Combine. Bad ideas result in bad stories, no matter who’s doing the writing. Rule 2: Listen and talk to the writer. Don’t nag, don’t hang over her shoulder. But do have a discourse. Challenge. Help the writer refine the idea. Rule 3: Read the damn story all the way through before you lay a pencil or a cursor on it. This seems like a simple matter, like medical personnel always washing their hands before they touch a patient, but you’d be surprised how often patients and stories get prematurely handled. Rule 4: Be gentle but be firm. Editing is a deep element of Time Inc. culture. There were guys from Time and Life magazines who used to say to writers, “Give me the bricks, I’ll build the story.” Thank goodness, that was never the rule at SI, though plenty of stories were thoroughly rewritten. When I was first at the magazine, the pieces of some writers, including one of the magazine’s most famous guys, were routinely and completely redone. But extensive rewriting was never the rule, and it became less frequent as the years passed and the depth of writing talent on the magazine increased. Stories written on deadline are also edited on deadline, and when the flawed story arrives on deadline there’s not much that the editor can do but have at it. There should be no need to do that on a non-deadline story, on which the writer and editor should be collaborators. I would say that a good editor can turn a weak story into a serviceable one but rarely, if ever, an excellent one. Conversely, a judicious editor (and a rigorous fact-checker) can mildly enhance a story that’s already good. And, yes, with the good and true story the editor should diligently try to preserve the writer’s voice, to retain the individuality of the piece. However, all this discussion of word-editing becomes moot when good writers are paired with good ideas. That means that hiring talented writers who are also tough reporters and then applying Rules 1, 2 and 3 will render Rule 4 irrelevant.

J.P.: Here’s something I’ve been dying to ask for years. When I got to SI, everyone spoke of the “Princeton pipeline.” I was asked, repeatedly, “How did a guy from Delaware get here?” And people would point out, “Look—this guy, that guy, that guy–all Princeton.” So … Peter, proud Tiger alum. Was there a leaning toward Princeton grads?

P.C.: Well, there was certainly once an Ivy League pipeline. The company was founded by two Yalies in the 1920s, and as late as my arrival there was clearly a penchant for hiring Ivy Leaguers, especially from the so-called Big Three. I recall that there were 12 other young men in the internship group with me in the summer of 1962, and, if memory serves, all of them came from Harvard, Princeton or Yale. Thank God, neither the “men” nor the “Big Three” part of that survived much longer. Certainly over the years Princeton was disproportionately represented on the editorial staff at SI. When I got to the magazine, I believe Frank Deford was the only Princetonian, but over the years the number increased until, I’d guess, that at one time in the 1990s there must have been eight or nine of us. As far as I know, this was not by design. Who wouldn’t have hired Frank or Alex Wolff or Ed Swift or Grant Wahl (and perhaps others whose names my aging brain can’t conjure up at this moment), who among them have written a significant number of the best articles to appear in SI. Bill Colson was a superb editor, as, I gather, Hank Hersh is now. I can’t recall ever hiring a Princetonian—the majority were brought in by chiefs of research who went to schools like Mount Holyoke and Michigan—though once they proved their worth, I was certainly eager that they be promoted, but I was no more eager for them to ascend the masthead than many, many more men and women from a lot of other schools whose roles were as central to SI’s success.

J.P.: I’ve long believed that diversity is important in sports journalism—because we’re covering such a diverse population. Yet SI has long been a place dominated by white males. I’m wondering, back in the day, whether that was a concern? Does it not matter, when the writing/reporting caliber is as strong as it was? Was it something you thought about?

P.C.: Damn right, I thought about it, and the company evinced concern. And it remains a frustration that we didn’t do better at diversifying the SI staff. As you suggest, diversity is important when you’re covering sports. I’d add that diversity is important, period. There may have been some mitigating factors here, but the bottom line is that we didn’t get the job done.

J.P.: Greatest moment of your journalism career? Lowest?

P.C.: The lowest is easy: When I wasn’t selected to be managing editor in 1984. There were a lot of high moments, some personal and most collaborative, but oddly the one I remember best occurred during the couple of years I left SI to be executive editor of Discover, the science magazine Time Inc. started in the early 1980s. The company made wholesale changes on the edit and publishing sides of the magazine in 1984-85 because Discover was both losing a fair amount of money and not very good editorially. In 1987 the magazine won the National Magazine Award for General Excellence, and I remember the managing editor, Gil Rogin, going to the podium to accept the plaque and saying something like, “Boy, we needed that.” Truth was, we merited the award. We’d turned the damn thing around.

J.P.: Do you think a print magazine can still matter, in the way print magazines once did? Can anything be done, or—a decade from now—is print dead?

P.C.: See my answer to your first question.

J.P.: If you can answer this one in the best detail possible—what was it like working at SI at its peak? I mean, what was the atmosphere? The mood? The feeling? Because I sorta fantasize about this place that, perhaps, I never fully knew …

P.C.: Do you watch Mad Men? Well, Don sits in what looks exactly like an assistant managing editor’s office from back in the 1960s, and Peggy has a senior writer’s office. There were bottles of booze in plain view on people’s desks and cigarettes in all 67 ashtrays on the conference room table during editorial meetings; there was a fair amount of fornicatin’ between members of the staff, and everybody knew who was screwing whom; you could buy a bag of really good shit, man, from the mail boy; on the weekends there was a fridge full of cans of Bud, just serve yourself; there was a bookie who arrived on the floor every Monday to collect debts; there was a poker game—a lot of seven-card high-low, a terrible game—in the TV room that started around nine Sunday night and often ended at dawn Monday that essentially financed Virginia’s and my social life; etc. For the younger staffers especially—the ones who didn’t have kids, who lived in Manhattan—the Thursday-to-Monday work week meant that SIers were sort of forced to become close friends, often best friends. The quality of the writing and photography was always a matter of serious discussion, and there was a clear, if unofficial, hierarchy among the writers and photographs; when I came to the magazine people bowed to writers like Jack Olsen and shooters like John Zimmerman, and throughout my time that sort of admiration for our fellows who were the best persisted. That says a lot about the general seriousness of the enterprise.

In those days there was a sort of intimacy on the staff that declined over the years. Until well after I joined SI, all the writers and most of the photographers lived in New York and came to the office on days when they didn’t have assignments. Each writer had a office on the 20th floor of the Time and Life Building, and until an uppity young writer started posting a note on his door saying, “Frank Deford is working at home,” most stories were written in office, no counting those deadline jobs that were wrought in hotel rooms, press center or bordellos and sent to the office via Western Union. Clearly the superficial aspects of the culture have greatly changed, and I think that’s largely for the better. Without the managing editorship of Andre Laguerre there would probably be no SI now. When he took over around 1960, SI had never made money and was of so little moment that a lot of people of Time Inc. thought the company should just fold the damn thing, which was then a mélange of Sport, Town and Country, and Betty Crocker. Andre and the guys he listened to (SI staffers, not the corporate higher-ups) understood the attraction of spectator sports and realized that sport’s popularity was soaring because of TV, which was then the bogeyman of the magazine business. In effect, Andre allied SI to its supposed enemy. The big events and big sports stars on TV became the games and people that SI featured in-depth, and the magazine, which already had a coterie of excellent writers and photographers, took off in terms of both prestige and loot. I had no role in this transformation. When I was working at the magazine in the summers of 1963 and 1964, Laguerre was a rather forbidding Gallic presence who wore a black suit, black tie and white shirt to work every day and silently strode the halls in shirtsleeves carrying a 3-foot-long stick with which he tapped the walls. He was revered in the office then (as he still should be today, for many reasons, not the least of which was his unbending dedication to maintaining editorial independence). When I returned from the service, the magazine’s transformation was essentially complete, but the triumphant Laguerre was a much less imposing man. His alcoholism now rendered him almost useless in the afternoon following his liquid midday repast; I can’t tell you how many times I heard an editor or layout artist say something like, “We’ve gotta get this to Andre before lunch, or it’s never gonna get done.” Andre was fired a couple of years later and died much too young. He was the most prominent and perhaps most tragic victim of the office culture of the time. I don’t know when the SI “peak” you mentioned occurred. When we started to make tons of money in the 1980s? When we won two National Magazine Awards for General Excellence during Mark Mulvoy’s dynamic tenure as managing editor. When guys like Deford, Rick Reilly and Gary Smith seemed to win the best writer awards every year? For me, the peak was when Andre and his staff went against the conventional wisdom of their time and showed themselves and us today that it could be done.

QUAZ EXPRESS WITH PETER CARRY:

• Five greatest sports journalists of your lifetime: I’m a wimp. I want to keep my friends. I take the fifth on the five.

• How often do you read Sports Illustrated in 2014?: I at least glance at it three weeks out of four.

• Rank in order (favorite to least): Spencer Haywood, Illinois State, Los Angeles Times, Instagram, Ray Combs, Elena Delle Donne, Connect Four, Yale, bottled water, clam chowder, Elijah Wood: I can’t rank these disparate items, but I can tell you what I think of them. I prefer to drink wine if my beverage has to come out of a bottle. New England clam chowder, yes; Manhattan clam chowder, no. I knew Spencer Deadwood pretty well, and Pete Vescey had him pegged right. I’ve read the L.A. Times, but probably not since the great Jim Murray died. I’ve not read a word of or watched a second of Lord of the Rings. I know that Ray Combs is no Richard Dawson. I have never sent or, I suspect, received an Instagram, except perhaps a retrospective shot of Doug Collins playing at Illinois State. Elena Delle Donne could shoot the J better than Collins or Deadwood. I learned one thing for sure at Princeton: Yale Sucks!

• Celine Dion calls. She wants you to serve as editor of her new magazine, “Celine Life.” You’ll make $30 million next year, but you have to move to Las Vegas, wear Gene Simmons’ face paint every day and watch Titanic three times per day. You in?: Is any of this negotiable?

• The most overused word in writing is?: I change the question to overused/misused. Sportswriting: “Great.” Writing: I’ve got a million pet peeves, but let’s try this: any present participle used to start a dependent clause: “Thinking he was the next Marcel Proust, he began to write his own remarkably tedious novel.”

• The biggest jerk athlete you ever interviewed was …: I refuse to slam the dead.

• Are you aware that, when we were called into your office to be edited, we stared at the photo of your beautiful daughter placed on your desk?: No, but I understand why. You oughta see her now. She has had twins, but she’s more of a knockout than ever.

• Three words you’d use to sum up your feelings for reality television?: Don’t watch it.

• Ever thought you were about to die in a plane crash? If so, what do you recall?: About 1998, I’m flying out of Detroit on an early plane back to New York to get to work on a Sunday morning after having gone to a family celebration at my brother’s house. Starboard engine goes up in a puff of smoke about 15 second after lift-off. Some of that puff of smoke passes through the cabin. I fear fire, which I know, because my father was in the aviation business, is the worst thing that can happen on a plane. But the smoke dissipates. There is no fire. People keen like mourners at an Irish funeral, I see rosary beads for the first time in years, but I’m pretty sure we’re OK. I know that the plane can make it to New York on one engine if it has too, and I can already feel the aircraft banking into a turn back to Detroit Metro. After waiting way too long—I’d guess three minutes—pilot announces what I’d already figured out. Weeping and shrieking don’t stop, however. I feel calm, until we hit the runway and I see our escort of what looks like around 100 yellow fire engines, red lights flashing, tearing down a parallel runway. We taxi back to the terminal. I get on the next flight. I arrive at the office a couple of hours late. I red pencil a story by Pearlman. That’s two scary incidents in one day.

• Why was Jimmy Carter such a meh president?: Actually he wasn’t so bad, but his nervous tic of a smile made everyone think he was out of touch, as in, “XXX of our people were taken captive in Iran today” [nervous smile]. He was smart as hell, but he was our only nerd president. However, he was perhaps our greatest ex-president. Nobel Prize-worthy.