When I was first promoted to staff writer at Sports Illustrated back in the late-1990s, a singular moment suggested I had made it.

Every Christmas, the magazine would fly in all the staff and senior writers for a big state-of-the-magazine meeting. We’d sit in a room, chat, then head out for fancy lunches with the top editors. I remember, quite vividly, my head spinning. I was Christian Laettner on the Dream Team. I mean, there was Rick Reilly! And Steve Rushin! And E.M. Swift! And Gary Smith! And Michael Bamberger! And Phil Taylor!

And … Michael Farber!

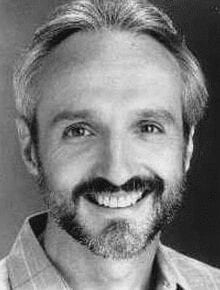

Man—Michael friggin’ Farber! The best of the best. A writer whose stuff I’d admired for years. And not only were we in the same room … we were at the same lunch. Sitting alongside one another, eating bread and stuff. And he knew who I was! By name!

Why the excitement? Because Michael, truly, is an all-time elite sportswriter; a guy who can make the least-interested hockey non-fan want to read a lengthy profile of the Islanders backup goaltender.

Michael has covered hockey for the Montreal Gazette and Sports Illustrated, and also serves as a member of the panel on TSN The Reporters. You can follow him on Twitter here.

Michael Farber, welcome to the Quaz …

JEFF PEARLMAN: I’m gonna start this with a random one, but something I’m happy to ask: So back in 1989, when I was writing for my high school newspaper, I interviewed Joe Bucchino, who lived locally and worked as the assistant general manager for the New York Rangers. I asked Joe specifically about the lack of blacks in hockey, and he told me blacks lacked the leg strength to be high-level players. Knowing nothing, I included that somewhere in the body of my article, some glowing profile read by 20 people. But I’ve never forgotten it, and I wonder, Mike, whether back in the day hockey had a legitimate problem with racism, stereotyping, etc. Or if this was simply one dumb guy spouting off his ignorance?

MICHAEL FARBER: I’d never heard any management person say anything quite that far out there, but certainly stereotyping was around then, and it hasn’t gone too far away. Maybe the stats revolution eventually will eradicate it forever, and one day a person will not be judged by his country on his passport—roll the stirring music in here—but by his Corsi or whatever.

Until then, some teams will shy away from Euros because they consider them “soft” or Russians because they are difficult, or enigmatic, as Churchill put it, or even young American players, who sometimes are considered entitled—at least by Canadians. A few years ago a Canadian assistant GM of an American-based NHL team told me he thought a forward we were discussing was “a typical American,” meaning the player had some skills but was not to be trusted in a crunch situation. Brian Burke, the Calgary Flames president and a man I consider a fried, used to refer to Sami Pahlson, who figured prominently on the Ducks checking line when Anaheim won the Stanley Cup in 2007, as a Swede who could have been born in Red Deer. This is more a compliment for western Canada than it is for the Tre Kronor.

You brought up black players specifically. Well, until the rise of the skilled black forwards in the late 1990s—think Anson Carter and especially Jarome Iginla, whose mother is white—many blacks in the NHL were either goalies like Grant Fuhr and Pokey Reddick or tough guys like Peter Worrell and Donald Brashear. The game has changed, personified by Montreal defenseman P.K. Subban. Whether you like him or not, Gary Bettman deserves at least a modicum of credit for a more open NHL. The commissioner has been the moving force in the league’s diversity program. Maybe someone else would have moved the infrastructure in that direction, but it would have been a long-time coming.

J.P.: In 2011 you were diagnosed with stage three mouth and throat cancer. 1. How did you find out? Were you experiencing difficulties eating, breathing? Was it out of the blue? 2. How did you process the information? 3. You’ve been given a clean bill of health—what has the battle been like? Highs? Lows? Realizations?

M.F.: In December of 2010, I was in Belfast, working on an SI story and also visiting my son, who was getting a master’s degree in the high-paying field of cultural anthropology and Irish music at Queen’s University there. I felt a lump in my neck on the left side. I made an appointment with an ENT in Montreal about six weeks later. I was seeing him on a Tuesday. On that Sunday morning, after brunch before the NHL All-Star game in Raleigh, I had a dear old friend, a doctor who lives in Winston-Salem, feel the lump. I got the “hmmmmmmm,” which pretty much was the clue that this wasn’t likely a cyst. After biopsies, CT scans and the like, I was diagnosed in mid-March.

Now this next part is critical. In early April at the Jewish General Hospital in Montreal, I had a salivary gland transfer operation, a procedure that was developed in Edmonton around 2003, I think. This surgery moves one of the glands out of the path of radiation and preserves saliva, which is a key lifestyle move. I know people who have had the cancer, been cured and then are miserable because they can barely eat or enjoy food. A woman I know lives on Ensure and ice cream. The procedure still is done infrequently in Canada and rarely in the States, if my Montreal docs are correct. That’s a shame. If anyone needs to go through this, ask about the possibility or availability of a salivary gland transfer.

Anyway—I’ll yada, yada, yada through some of it—I had a feeding tube installed, went through six chemo sessions and six weeks of radiation and came out the other side. The treatment was Hobbesian—nasty, brutish and fortunately short. My treatments finished June 6, 2011, and I remain cancer free with a good prognosis. Feeling great. I haven’t had any alcohol since my diagnosis—alcohol and throat cancer are not a good mix—and I have trouble with peppery or spicy food, but I couldn’t be better.

Thanks for asking. I used to get asked if cancer had changed my perspective on life. Nah, I think my priorities were in order before my cancer. Anyway, in May 2014, I was honored by the Jewish General Hospital, for living, I assume, and we raised almost $600,000 in a fundraiser. Guy Lafleur, Larry Robinson and some other hockey folks were there. The Hockey Hall of Fame sent the Stanley Cup for the evening. If any Quaz reader wants to write a check to the McGill Head and Neck Cancer Fund, I’d be grateful.

J.P.: Magazines aren’t what they were. Not when I started at SI in 1996, not when you started there in 1994. So, I ask, what was Sports Illustrated when you started there? What I mean is, what did it mean to you to work there? Did it feel glamorous? Meaningful? What was the buzz? The perks? And do you feel like, with the death of print, that sort of thing is forever gone?

M.F.: Actually, I turned down SI the first time it asked me, in August 1989. This was weird. Within three days, I had calls from Frank Deford, then at The National, and Mark Mulvoy, at Sports Illustrated, about coming aboard. The job at The National, basically as a hockey info guy, didn’t interest me, but SI did. But ultimately the timing didn’t seem right. SI had been through a ton of hockey writers after Ed Swift started doing some other things and none had lasted. So I passed.

But SI was starting SI Canada—I moved here in 1979 to work at The Montreal Gazette—and asked if I would do some freelance stuff. My first piece for the magazine—Gary Payton on the cover—was why no baseball players wanted to play in Montreal and no hockey players wanted to play in Quebec City. October 1989, I think. Then in 1990 the Canadian edition started and I did a few SI Canada stories a year. I was covering the World Series in Philly in 1993 for The Gazette when Mulvoy asked if I could come to New York immediately. I had been on the road for almost a month and told him I needed to get home after the Series ended, but I’d be down right after. I flew down in late October, shot the breeze in his office for 10 minutes and then flew home. That was my SI WTF moment. No offer. Nothing. Then six weeks later, I get another call from Mark asking me if I could fly down. I mumbled something about just having been there six weeks ago, but he said, no, no, I gotta to talk to you. Well, OK. I have no idea what happened then and what changed in the interim, and I have never asked. But this time he made an offer, and I took it.

My situation had changed. My mother and grandmother had died that year, and I had some heart issues during the 1993 Stanley Cup final and again at the Series. I needed a change, which included the “leisurely” magazine life. And compared to a newspaper column, it was leisurely—at least for a few years. I don’t know if 1994 was still the golden time at the magazine, but SI hired the fabulous S.L. Price, the invaluable Tim Layden and the talented Gerry Callahan in the following months, so that was a pretty good class to be part of. That’s the best part of the SI experience: the people you get to work with.

The secret of journalism is good stories, well told. Always was. Always will be. Now we’re just sorting out the delivery systems. But I will say this, and I suspect you feel that way too: when your name is in the masthead with the likes of Leigh Montville and Bill Nack and Steve Rushin and Tom Verducci and Jack McCallum and Rick Hoffer and Lee Jenkins on and on, that’s pretty good, no?

J.P.: I’ve long considered you one of the great sports writers of our era, and I’m fascinated by the process. Your process. For example, there’s a young player you’ve been assigned to profile. You have a week or so. What’s the approach? How do you go about it?

M.F.: I am a pretty fast writer, a holdover from my newspaper days, but a really slow thinker. So I will do all the background stuff that anyone does when he is assigned a story: calling his junior coach, his parents, old teammates, whomever. Basic homework. But while I’m checking off the boxes, I’m thinking about words or phrases or thoughts and polishing them in my mind and thinking where they might fit in the structure of the 2,000 words.

When I started at SI, I wrote too many “scene” leads, probably because I had read so many in the magazine. A scene lead isn’t necessarily bad way to go, but after a few years I started dropping more idea leads onto the editors. Bam. Just start the piece. Also after my healthy issues—I had a quadruple bypass in 2002—I also gave myself a little more time to do the actual writing. I can rush, but I hate doing it. My only real quirk, I suppose, came in my newspaper days when we wrote on typewriters and used carbon paper. After finishing a story, I would physically move to another desk in the office to edit it. I thought it would give me a different perspective. What an idiot.

J.P.: So I know you’re from Bayonne, N.J., know you were fantastic as a reporter and columnist at the Montreal Gazette, a killer writer at SI. But … how did this happen to you? When did you know you wanted to be a journalist? What was the spark? Who was the inspiration? And why hockey?

M.F.: I stumbled into hockey, really. In fact, when I moved to Montreal in 1979, when the Expos were coming into in their prime, I was sort of a baseball guy. Of course growing up near a city like New York, you follow all the sports. So the Rangers were the winter thing—I liked the Celtics, not the Knicks—and I was always comfortable around the sport even if I never played anything other than street hockey. In fact I covered the Rangers the year of the Phil Esposito trade for The Record in Bergen County. But when you move to Montreal, you’d better be prepared to become a hockey guy. Fortunately I had a heritage franchise to write about, one filled with smart and often loquacious players—a little like the Islanders team of the late 1970s and early 80s. I knew sportswriting was something that I wanted to do since my freshman year at Rutgers, where I worked in the Sports Information office. Hockey turned out to be a happy accident.

J.P.: I hate to be clichéd, but I’ll be clichéd: Hockey isn’t huge in the U.S., the way football and basketball and baseball are huge. And I don’t get it, because the sport is ridiculously exciting, the players tend to be agreeable and accessible, the uniforms are cool, the ice arenas are splendid. So … why hasn’t it fully caught on? What’s wrong with us?

M.F.: It’s funny because the Rangers have been around since 1926 and yet even some editors down 20 blocks in midtown in the SI view hockey as somehow exotic. This is especially odd because Mark Mulvoy had been the hockey writer, current top editor Paul Fichtenbaum was my first hockey editor and Chris Stone, who runs the mag on a daily basis, was a hockey reporter.

Some of hockey’s problems are the stuff we’ve all heard—can’t see the puck, etc.—but consider this: LeBron James plays maybe 40 minutes a game and has the ball in his hands almost every possession. In hockey, Sidney Crosby might play 20 or so minutes, his head covered with a helmet and his face obscured by a shield, and the puck will be on his stick for less than a minute. Tough to build a sport around stars, especially in an era when offense has returned to old, historic averages and no one can put up Gretzky-Lemieux-Nintendo numbers any more.

I also think the sports opinion makers in the States—Kornheiser and Simmons and those folks—are less comfortable or knowledgeable about the sport and therefore, wisely, in my opinion, talk about it occasionally. Other than Tim Colishaw and Jeff Schultz, how many top newspaper columnists came out of the hockey beat? Dave Anderson did. Bob Verdi did. I’m sure I’m missing someone. Anyway, this reinforces the notion that hockey just doesn’t matter. ESPN will be airing the 2016 World Cup, and I noticed it beefed up its coverage last spring. In SI I once referred to hockey as the NASCAR of the north, a niche sport, but at the time NASCAR was drawing bigger TV numbers. Now if you toss out the border and examine hockey’s appeal across the U.S. and Canada, then the discussion tilts, at least a little.

J.P.: Greatest moment of your career? Lowest?

M.F.: I’m not sure what the greatest moment is. Being honored by the Hockey Hall of Fame with the Elmer Ferguson Award in 2003 for hockey writing? Dunno.

I can tell you the lowest. Between the fall of 1984 and February 1988, I was writing a city column five days a week for The Gazette. The column was a disaster, in my opinion, in part because my French was really weak and in part because it was a column that was neither fish nor fowl, not courts nor lifestyle nor much of anything really. In almost four years I wrote only a handful of Grade-A stuff, including one piece on “a bleeding” religious statue. I also wrote what should have been a nice story on a diabetic doctor who continued to treat patients after she lost her eyesight. And I spelled her name wrong. Can you believe that? I’m still not over it.

J.P.: I read an article about you from 2014, and you said, “I’m pretty optimistic about everything. I wake up every day and I almost never think of my cancer.” So this is sort of random, but I think about death pretty much every day. The inevitability. The eternal nothingness. It haunts me in unhealthy ways … and I haven’t been diagnosed with anything. So how have you been able to put cancer out of your mind? Does mortality and the fleetingness of life not scare you? Is it a matter of faith? Of contentment? Because, whatever you have, I envy …

M.F.: I have a great wife, two really interesting and, in different ways, accomplished children. (My son is getting his doctorate while teaching history at Dawson College in Montreal, and my trilingual daughter is a journalist working on the English side of Agence France Presse’s Moscow bureau.) I have two grandkids. This quasi-retirement thing is going pretty well; I’m doing some typing for SI and some television in Canada and a little consulting on NBC’s hockey rivalry shows.

I mention my Carolina doctor friend again. When SI was offering buyouts in 2012, I called him and asked what he thought. I was not quite 61 at the time. He said, “Well, what do you plan to do with the last 10 years of your life?” That really hit me. After another WTF moment, he calmly explained that given my family history, I could expect to live a pretty good and active life until 70 but then some sliding was probable if not inevitable. Right. So I decided I didn’t want to spend one weekend in Dallas, the next in Detroit, etc. I checked out of the full-time job. Look, my father died at 29. His father died at 29. Heart stuff. I turn 64 this month and I’m still here. Unless I’ve been misinformed, you get only one shot at life. So Jeff, kindly cheer the fuck up.

J.P.: Have sports gone too far? The merchandising, the loud music at all times, the me-me-me reaction to scoring a goal, the sports parents thinking their 3rd grader is the next Nick Foles? Do you think athletics have crossed a line of self-indulgence, or over importance? Or am I just a cranky old man?

M.F.: Funny, my daughter had never been to an NBA game so one Sunday I flew her from Ottawa, where she was going to university, to Toronto for a Raptors game. She is a sports kid, a decent soccer player who knows her hockey, but she was left cold by the game because, she said, “it’s more like a show than a sport.” She meant the music playing while a team was coming up court and the dance teams and such. I used to like the halftimes at Celtics games at Boston Garden where I was perfectly content to talk to a buddy while the organ played and the players came back on the parquet with four minutes to shoot before the second half tipoff.

The self-celebration grates on my sensibility—these songs of myself have long past an expiration date—but then when I first started writing, stringing Rutgers football for UPI in 1970, I actually typed my copy and drove it to the Western Union office in New Brunswick. I think the most damaging part of all of this is the specialization by kids. Wayne Gretzky played sports according to the season. So did Paul Kariya. Let kids be kids. Of course if my daughter had had Mia Hamm talent instead of being undersized goalkeeper who sat on the bench in university, maybe I would have felt differently.

J.P.: What are the keys to reporting an event when 800 other reporters are covering the same event? How can one get unique information, fresh material?

M.F.: I’m not sure I ever found the key to covering an event, on a magazine deadline, and finding the one little nugget that eluded everyone else and that would still remain uncovered four days later when SI appeared. Maybe a snippet of institutional knowledge helped or having a contact because I’ve become a familiar face around NHL rinks, but frankly I’m just not that good of a reporter. I think the key is seeing something that is hiding in plain sight. Making a connection that someone else might not. Maybe it’s an idea I have. Or maybe it’s typing the story a little better than the other guy. I used to think I could outwork people but the writers who grew up in the Internet Age work harder than I ever did.

QUAZ EXPRESS WITH MICHAEL FARBER:

• Four memories from your Bar Mitzvah: Don’t remember much about my Bar Mitzvah. I did get through the Haftorah without my voice breaking, so that was good. Also there was a little luncheon at the synagogue after the ceremony. Pretty low key.

• Most embarrassing moment of your journalism career: The doctor’s name.

• Rank in order (favorite to least): Larry Robinson, Kevin Mench, Sade, Grant Fuhr, “The Usual Suspects,” Yellowknife, Sharon Stone, your nose, SportsCenter, chicken soup, Wesley Walker: Larry Robinson, Grant Fuhr, Sharon Stone, TSN’s SportsCentre (in Canada, that’s the spelling), chicken soup, The Usual Suspects, my nose, Wesley Walker, Yellowknife, Kevin Mench, Sade.

• Five greatest hockey players of your lifetime: Bobby Orr, Wayne Gretzky, Gordie Howe, Mario Lemieux, Jean Béliveau.

• In exactly 22 words, break down Michael Farber’s hockey skills: Zero, zip, nada. The last time I was on skates was 1985, skating with Orr at the Forum in a charity event.

• Would you rather permanently change your name to Asshole Seven or have Shea Weber shoot a puck at your privates from 5 yards away?: Shea Weber. I’ll be wearing a cup.

• Who is the most underrated NHL player during your career?: Sergei Zubov.

• Best joke you know: A well-dressed man is walking down the street. A beggar stops him and asks to borrow a quarter for a cup of coffee. The well-dressed man says. “Neither a borrower nor a lender be … William Shakespeare.” The beggar replies, “Fuck you … David Mamet.”

• How do you feel about Twitter?: I enjoy Twitter, not because I tweet much but because it alerts me to breaking news or stories I might otherwise miss.

• You need to interview an athlete. He’s intimidating and a known asshole. How do you approach?: Are you sure I’m not an intimidating asshole?