For those of us who were fortunate enough to grow up reading Sports Illustrated, then write for the magazine, there’s this oft-unspoken ranking thing that happens inside our heads.

Without fail, we all have our, “Top 5 All-Time Sports Illustrated greats” lists. The names tend to vary from person to person. My Frank Deford is your Dan Jenkins is your Steve Rushin is your Rick Reilly is your Bill Nack. One person, however, who seems to cross the lines of age, gender, race, area of specialty is Alexander Wolff.

Beginning in 1980, shortly after his graduation from Princeton, Alex joined the staff of Sports Illustrated. He then spent the next three decades writing some of the most beautiful, most comprehensive, most intelligent pieces in modern sports journalism. He’s covered everything, from the Olympics to the World Series, but is best known for his devotion to chronicling basketball. Of John Wooden’s 2010 passing, for example, Alex wrote: “If death had granted him a moment to convey the sentiment, John Wooden would have declared his passing last week at age 99 a happy transit.” Of the 1982 Dallas Mavericks, he observed, “To paraphrase that great Irish hoop maven, Willie B. Yeats, things can fall apart if your center’s no good. That summarizes the prospects of the Dallas Mavericks in their third season.” Seriously, tale a moment and check out the scope of his work on the SI Vault. It’s gold.

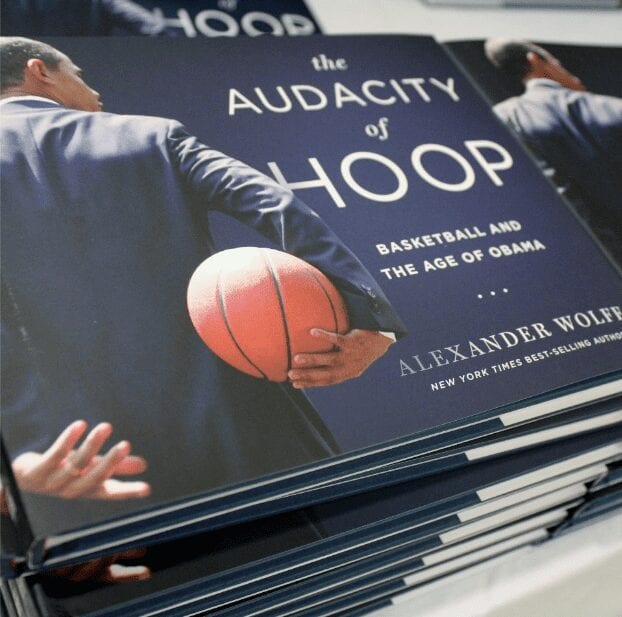

Though he’s officially listed as retired on the scouting report, Alex still contributes to SI. He’s also the author of a wonderful new book, “The Audacity of Hoop,” on Barack Obama’s devotion to basketball.

One can follow Alex on Twitter here.

Alexander Wolff, you are the Lancaster Gordon of writers, and the 288th of Quazes …

JEFF PEARLMAN: Alex, I’m gonna kick this off with a depressing one. Yesterday Sports Illustrated laid off more employees. Inevitably they were lay off more, and more and more. It strikes me that this can’t end well; that maybe there’s just no saving print and the magazine is a dinosaur scheduled for inevitable extinction. You worked at the magazine for decades. You were there through some glorious years. Do you have any hope? How does it all make you feel?

ALEXANDER WOLFF: I was an SI fact-checker in the Bright Lights, Big City days, and then a writer on staff into the early 2000s, when the magazine and travel budgets were fat and if you threw out a story idea you’d hear back, “When can we have it?” And then I spent the last decade or so until retirement just trying to breast the tape as bodies collapsed around me. So this is a painful subject.

But even as this agonizing transition from print to digital takes place, I have to believe there’ll still be an appetite for the mag. It may be a mag that appears less often than every week. It may be one produced with contributing rather than staff writers; some of the photographers who lost staff gigs a few years ago are now getting even more SI work as freelancers. The people who are still on staff are top-of-the-craft. Just from a hoops perspective, it doesn’t get better than Lee Jenkins and Chris Ballard on the pros, and Luke Winn and Seth Davis on the colleges. With a little help from my son, Grant Wahl has turned me into a soccer fan. Tom Verducci and Peter King are the voices of their respective sports. And guys like Tim Layden and Scott Price and Jon Wertheim and Mike Rosenberg are just absurdly versatile.

Which is why it hurts so much. No one let go over the past dozen years or so was sacrificed at the altar of anything but Forces We Can’t Control. They were universally smart, gifted, productive people. Many—I wish I could confidently say “most”—have found other places to commit journalism. That’s our loss and others’ gain, but at least the same forces threatening the SI so many people grew up with are creating all these new soapboxes in the public square that people can mount and speak from.

My hope rests in technology and new norms it may set. In 10 or 15 years we may all keep rolled up in our pocket a paper-thin device that captures and displays words and pictures instantaneously, a kind of turbo-charged iPad, and if so SI will be right there, delivering first-rate content by talented people, and the brand will endure—not because people have accommodated themselves to us, but because we’ve been nimble enough to go where the consumption is, whether it’s on a Web-enabled fruit rollup or whatever.

Just last week I had a feature in the mag about cord-cutting and “over-the-top” delivery options, and how leagues and networks are being forced to move to the platforms people choose to spend time on. The challenge facing print is pretty much the same. People will always want a good story well-told, and I’m never going to doubt SI’s ability to deliver that regardless of the platform. My fear is the same one I and many others expressed in last week’s piece, for rights holders and their broadcast partners: all the dislocation along the way.

J.P.: You’re best known for your work on basketball. I have this thing in my head, that the college games was never better than it was in the 1980s in the Big East. Mullin, Ewing, Pearl, Billy Donovan, Cliff Robinson, on and on. But am I just falsely glorifying something from my youth? Is it better in my mind than it was in actuality?

A.W.: I’m as susceptible as you to romanticizing those days, because I was young and impressionable and just breaking in. I had a chance to take stock a few years ago while working on a piece about the demise of the Big East, and it was a stitch to collect stories like the one about God Shammgod as a freshman at Providence, walking into a religion class and, asked to introduce himself, saying, “My name is God Shammgod and I’m here to take Providence to the Promised Land.” Which led the priest teaching the class to call the college president to find out what in Jesus, Mary and Joseph was going on.

But the sport was great everywhere during the Eighties. It was growing with ESPN and worming its way into every corner of the country. For you it might have been the Big East, but I was even more smitten by the SEC of that era, maybe because the South seemed so exotic to a kid from the Northeast, and maybe because the basketball coaches had to work extra-hard to catch anyone’s attention what with the football emphasis. You had big, bad Kentucky, the team everyone was shooting for. At Auburn you had Charles Barkley, and Tennessee students delivering a pizza to him in the pregame layup line. LSU started at forward a guy named Nikita Wilson, whose middle name was Francisco, which led Mark Bradley of the Atlanta Journal-Constitution to call him “a trilateral summit conference.” And the coaches had this honor-among-thieves camaraderie. I loved the wit of Georgia’s Hugh Durham and Auburn’s Sonny Smith. Alabama’s Wimp Sanderson was, in his words, “named after a cousin who blocked a punt and died shortly thereafter.” At one SEC tournament LSU’s Dale Brown pledged not to sleep for the entirety of the four-day weekend and then phoned writers at all hours to prove that he was keeping his word. It was the cheating-est league in America. Probably still is. But in terms of pure entertainment value, every dollar was well-spent.

J.P.: You were the owner of the Vermont Frost Heaves of the ABA. It started as a magazine idea, then just got really interesting. I’m gonna be vague and wide open here. How did the idea begin? Why? And what did you learn/gain from the experience?

A.W.: One of my professional vices has always been a certain restlessness. By the mid-2000s the basketball beat had begun to seem a little like Groundhog Day. I heard from NBA scouting director Marty Blake about the reconstituted ABA, where franchises went for $5,000. My wife and I had just moved to Vermont, and the Web was creating this limitless place for content. So the idea of starting a team and writing about it became hard to resist. And when I saw two great old Palestra-like venues in the Vermont cities of Burlington and Barre, I got sucked deep into the vortex. The hardest part was conceiving the project—and pitching it to editors—as this light romp through the theme park of pro team ownership, and discovering very quickly that there were real people with real stakes depending on the whole experiment working out.

I learned a lot about the goodwill of my Vermont neighbors, and how quickly money can disappear, and the incredible amount of work that goes on before a sportswriter sits down courtside in front of that little welcome card with your name on it. We rented the hall and paid the entertainment and basically threw parties for more than 1,000 people 18 times a year for three years. It wasn’t a sustainable financial success, but with two ABA titles and memories that people up here still talk about, it was an artistic one. The young Vermont guy our fans picked to be the coach, Will Voigt, just led Nigeria to the Rio Olympics. And Ken Squier, the old CBS motorsports analyst who runs the Thunder Road racetrack in central Vermont, so loved our mascot that after we folded he took Bump the Moose in like a stray. Bump is now Speed Bump the Racing Moose.

I wrote up 15,000 words for the SI.com longform site about the whole experience, but have another 50,000 or so stashed away. Even if that overset never gets published, writing it all up was therapy.

J.P.: You’re the author of “The Audacity of Hoop,” a new book about President Obama and basketball. Like me with Brett Favre, you actually never got to interview Obama for the project. So I ask: A. How did you go about trying? B. How did it impact the final product? And how did you even come up with the idea for this?

A.W.: Hoop had become such a big theme during Obama’s 2008 campaign that, after his election, I asked editors at SI whether they wanted a sort of basketball biography of him to run before the inauguration. After filing the story, I asked myself whether hoop would continue to figure in his life as president. And when it did—and all these great images from White House photographer Pete Souza began surfacing that featured POTUS around the game and NBA players—I began to think there might be a book. Of course, he needed to get re-elected for it to have any chance in the marketplace. But after he was, I threw myself into the project.

There’s no way to badger the President of the United States for an interview without bringing yourself to the attention of the authorities. So I put in my request, hoped for the best, and got on with the project. A little part of me died each time he’d sit down with Bill Simmons for the umpteenth time, or make a sidetrip to Marc Maron’s garage for a podcast, and my own phone wouldn’t ring. But Obama has left a long trail of commentary about the game, none better than those pages in his memoir Dreams from My Father, so there was that to work with.

And as you know from your Favre experience, even with the hole, there’s something to the donut. Not getting your main subject forces you to work the edges that much more. And like you with Favre, I benefited from there being no active effort to keep me from doing the book. People in the Obama hoop circle spoke openly and freely. And I did feel I got cooperation from the White House to the extent that Pete Souza chased down images we were looking for. One of my favorites has POTUS dribbling toward the camera with his daughters on either side of him. He’s dribbling with his weak-ass right hand, as are Malia and Sasha, and it’s an incredibly poignant photo if you know the Obama backstory: POTUS has said that he might have been a better player if he’d had a father around to take him out to work on his off hand. I have no idea whether his girls are right- or left-handed, but here Obama is discharging his paternal duty with them both, taking care of business his own dad never tended to.

And in one respect I got the ultimate cooperation: Throughout the Obamas’ time in Washington, the White House has been loath to release photos of the girls. But Souza said he’d try to get authorization for us to use that shot, and came back with a green light. You can take it to the bank that either POTUS or FLOTUS signed off on it.

J.P.: How did this happen to you? I mean, I know you grew up in Princeton until age 12, then moved to Rochester; know you had your first byline taste in the Trenton Times, know you attended Princeton, graduated in 1979, joined SI a year later. But when did you know writing was for you? Was there a moment? An event?

A.W.: I grew up around words and just learned to love them. My grandparents were book publishers, and even my dad, an English-as-a-second-language immigrant who was 28 when he arrived from Europe, lit up when he saw a Puns & Anagrams puzzle in the New York Times. I consumed any newspaper or magazine that made it into our house. But I was indiscriminate with language, and it took a ruthless English teacher to shake some of the lassitude out of me during my sophomore year in high school.

But it was four years later, in a writing course at Princeton, that I really got excited about journalism. It’s the course that John McPhee still teaches today, though he didn’t teach it that semester because he was off working on his Alaska book, Coming Into the Country. Robert Massie, the old Newsweek and Saturday Evening Post staffer who had gone on to write Nicholas and Alexandra, took his place, and he was a great fit for a kid who was about to be a history major. The 16 of us in the class would get our one-on-one time with him, going over what we wrote, but the real value was in reading and critiquing what others produced. I went back to campus 20 years later to teach a similar course, and the magic around that seminar table—a gentle peer pressure, but of the pressure-makes-diamonds kind—was still an animating force.

Meantime I’d joined a group of campus stringers and begun filing for the Trenton Times, which was 12 miles down Route 1. Because it was so close to campus, editors would take just about anything. And because it was a p.m., I could stay up fiddling with my copy all night if I wanted, as long as I filed by the time the editors came in at 6. So I wrote a lot—some sports, but mostly news, arts and features. My stuff got professionally edited, and I could cross Nassau Street in the afternoon and pick up a copy of the paper and see exactly what had been changed. I even got a check every month. Princeton had no journalism major or school, but those opportunities were in place, and by taking advantage of them I got a glimpse of how I might make a living—and I quickly learned to like the variety and rhythm and satisfaction of it.

J.P.: In 1984 you wrote a cover story about a Chicago Bulls rookie named Michael Jordan. The team sucked, his greatness wasn’t yet established. What do you recall from that experience? Of a young MJ? And was it clear back then that he would be THIS good? Or was it more like, “If he works hard, he has a chance to be a Sidney Moncrief or Otis Birdsong-type player”?

A.W.: I’m not sure I accept the premise. By the time of that ’84 cover story, Jordan was the buzz of the league. Certainly Nike had already made the bet that he was on his way.

I remember the exact moment I knew. It was in Cole Field House his junior year. Carolina was playing that Maryland team with Len Bias, nothing close to an easy out. But the Tar Heels were in control from the jump, and Jordan seemed to elevate just an inch or two higher and hang for a quarter- or half-second longer than anyone else on the floor. He did just about anything he wanted. Late in the second half some Terp threw a lazy pass to the wing, and Jordan jumped all over it and turned it into an exclamation point slam at the other end. I still remember being gathered around his locker afterward, when someone asked, “Were you trying to send a message with that dunk?”

“No messages,” he replied. He sounded all business, like an efficient secretary. That day, that’s when I knew.

I make no claim to being a great judge of talent. I thought Lancaster Gordon was can’t-miss. But from watching Jordan in college, even in that supposed straitjacket Dean Smith cloaked his guys in, I knew Jordan would have his way with the league. I even shook my head when two big guys went ahead of him in the draft.

J.P.: I have a thing in my head, and it’s this: Most Division I men’s college basketball coaches are slime. Happy to break rules, happy to use kids until they can no longer be used, much more concerned with the next job than developing men. Am I off on this? On? Are there more exceptions than I think?

A.W.: Actually, if we’re going to slander entire professions, let’s go after college football coaches. They’re imperious and self-important and even more extravagantly overpaid, with no more refined sense of loyalty than basketball coaches. At least basketball coaches know their guys—three to five in a typical class. Woody Hayes had a starting quarterback hurt in the middle of one game and famously sent in a backup whose name he didn’t know.

I don’t see how you can care about a player if you don’t have more than a nodding relationship with him. And how can you really know a kid if he’s one of a hundred, and there are layers of middle-management (this coordinator, that coordinator, outside linebackers coach, inside linebackers coach) between you and them? Yes, there are on-the-make college basketball coaches, and plenty who’ll light out for a better situation without a care for who’s left in the lurch. But the haughtiness that permeates big-time college football right now is breathtaking.

Remember Dabo Swinney on that John Oliver segment, grumbling about the “attitude of entitlement” he thinks infects kids these days? You want to see entitlement, take a look in the mirror, my man. And if Title IX or some other nefarious equity ethic steers any bowl money to the women or non-revenue men, the tantrums these guys throw. Give me John McKay, the old Southern Cal football coach. He said he only needed three platoons: an offensive team, a defensive team, and a team “to carry me off the field after we win.” A-friggin’-men.

J.P.: You left Princeton after your sophomore year to spend a season playing for a third-division team in Lucerne, Switzerland. You had been merely an OK high school player. Um, how did this happen? And what do you remember from the experience?

A.W.: I was ready to “stop out” of college after two years, probably from some of the same restlessness that led to the Frost Heaves. This was back before even middle-schoolers talked about taking a “gap year,” and the concept was kind of revolutionary. A childhood friend, a Swiss-American, had played for the national junior team over there and was in college himself, in Fribourg, which happened to be where the Swiss Basketball Federation was based. The president of the federation wanted to develop hoop in the German-speaking part of the country, so my buddy passed along my name. I’d been the fifth option on my high school team, 6 feet tall and maybe 150 pounds, but I was American. When I got off the train in Lucerne, Andre, the G.M. who met me, must have been mortified. But third division club ball in Switzerland in the late Seventies was pretty crude, and I was as much a development worker as a ringer.

The club got me a nonverbal job working for an agricultural consulting firm, coloring maps to indicate soil aptitudes. I reffed rec league games around the canton and picked up a little more money that way. I read a lot. And I taught myself German, though I would have picked up a lot more if they didn’t speak that bizarre Swiss dialect.

When I returned to college the following fall I was much more mature and worldly. I’d like to say I caught a glimpse of the Euro-revolution that would remake the NBA. But mostly I was explaining to people who were conditioned to think of basketball as “not soccer” that it’s only a violation if you intentionally gain some advantage by striking the ball with your feet.

J.P.: What are the keys to reporting a great story? I know that’s a wide-open question, but … for you … what are you trying to do?

A.W.: It starts with the idea. If you have a notion for a story but struggle finding an entry point, or people to talk to, or simply what would go into a nut graf, heed those warning signs. There may be no there there. The last couple of decades I’ve done a lot of historical and issues-based pieces, and for both I’ll try to read widely before I do any interviewing—books and what I can find online, deadlines permitting. That helps with the inevitable passages where you set context, and it wins you goodwill when you go out to report because people know right away that you’ve done your homework and reached some threshold of giving a damn. For similar reasons, I try to swing by a library or historical society or archive once I’m out in the field. It’s amazing what gets stashed in those places, and how much the people who staff them know. Even if you only find one little fact, sometimes you can spin it into gold.

I had three days to turn around that cover story we did in the mid-Nineties urging Miami to drop football, and the most valuable time I spent was dipping into Robin Lester’s book about Robert Maynard Hutchins, the president of the University of Chicago who abolished football there. Hutchins’ son-in-law was the Miami president, so for my open letter to him I could deploy old Hutchins comments about the damage that football run amok could do to a university, and know they’d have real power.

Another strategy that has worked well for me is to make sure to speak to the women around a male athlete or coach. It’s just the nature of things that most of our profile subjects are men, and male athletes are conditioned to put up a shield and resist being introspective or showing vulnerability. Wife, girlfriend, sister, aunt, grandmother—they’re the proxies who can speak to that stuff, the ones who kept the scrapbooks and dressed the skinned knees and remember every little setback along the way. And I think male and female readers alike kindle to something emotional, like a story out of childhood, or proof that even today’s hero was once a goat.

The test around the SI offices after someone filed a profile was simple: Does the story answer the question, “What’s he like?” Understanding that you can never flesh out someone’s whole bio in one magazine story, that’s still the test.

J.P.: I feel like all of us who do this long enough have a money story—that one thing we can tell at parties for years to come. For example, I’ve gotten tons of mileage out of the whole John Rocker saga. So what’s your money story? Craziest, weirdest, most-memorable experience from your life? Do tell …

A.W.: Actually, that Miami story might have been my Rocker moment. It hits, and all of Canes Land is in an uproar. I’m this bogeyman for Miami fans and an easy target for harassment. A drive-time radio jock cold calls my apartment early in the morning, live. I’d gotten smart enough not to pick up, but my answering machine greeting was “You’ve reached 212-blah-blah-blah. I’m sorry I’m not here to take your call . . ..” Which meant that my home number was broadcast all over South Florida, which touched off another round of abusive calls. The weirdest thing is that, in an enemy-of-my-enemy-is-my-friend twist, years later Nevin Shapiro decides to write me from prison because he wants to dish on his adventures in unrestrained Miami boosterdom and figures I can be trusted. I really bear no ill will toward Miami. Sometimes assignments just break a certain way.

For entertainment value at a party, though, I’ll default to something that happened while covering the Bulls during a late-Nineties playoff series. I find myself in the back seat of a car leaving a downtown Chicago club at 3 in the morning. Dennis Rodman is at the wheel. Carmen Electra is riding shotgun. He patches out, backward, down three city blocks, oblivious to the lights, then hits 90 on the Dan Ryan. She’s egging him on the whole way. I’m terrified, envisioning the headline: RODMAN, ELECTRA, ONE OTHER, DEAD IN CRASH.

QUAZ EXPRESS WITH ALEXANDER WOLFF:

• Rank in order (most desirable to least desirable), guys you can start a team with (from their primes): Fennis Dembo, Yinka Dare, Gerry McNamara, David Wingate, Lancaster Gordon, Laron Profit, Kit Mueller, Shawn Respert, Adam Keefe, Vin Baker: Baker, Respert, Gordon, Keefe, Profit, Dembo, Wingate, Dare, McNamara, Mueller (My head’s spinning from two Lancaster Gordon refs in one Quaz).

• Why wasn’t Reggie Williams a great NBA player?: He was a stick. George Gervin was the last real bag of bones to make it big, and Ice had that one signature shot. Great NBA players all have some signature shot or move, a little film clip that plays on your frontal lobe when his name is mentioned. Reggie didn’t really have that. (That little flip from along the baseline doesn’t count.)

If Reggie had come from some compass-point school in Michigan the way Gervin did, he might have developed a signature weapon. But at Georgetown he was a cog in a machine.

• Ever thought you were about to die in a plane crash? If so, what do you recall?: Leaving Denver on American, sitting in the back of the plane, there’s a loud pop from one of the two side rear engines just as we’ve taken off. Gulps all around the cabin, and the captain comes on, in that Chuck Yeager voice that Tom Wolfe wrote about in The Right Stuff: “Looks like we’ve had a little engine stall, so we’re going to circle back to the airport just to be on the safe side.” I’m no aeronautics whiz, but “engine stall” and “takeoff” would not seem to be an ideal combination. We make it safely back to DIA—I’ve always been grateful they didn’t name the place Denver Overseas Airport—and they subbed out the aircraft.

I do remember getting upgraded on that next flight.

• Our former SI colleague, Merrell Noden, died last year at 59. What can you tell me about him?: Merrell was an endlessly curious guy and a lovely writer who put up on a pedestal every one of the many people he counted as friends. There’s that Billy Collins line that “experience holds its graduation at the grave,” and Merrell was a great example. All the things you and I might have tried out through college, he was doing until the end. Taking piano lessons. Auditing math classes. Tutoring prisoners. Acting in a Shakespeare production. All while raising two magnificent kids and being a proud and supportive companion of his artist wife Eva.

• What’s the scouting report on Alexander Wolff, basketball player, 2016?: Can’t play without at least two days’ rest, ideally three. Only real shot is a square-up mid-range jumper. Beyond-the-arc range disappeared a dozen years ago, along with my core. Trying to backfill with “old man game,” but a guy needs more girth and better peripheral vision to really unlock OMG. Basically, more than 40 years after turning the age Janis Ian sang about in At Seventeen, now one of “those whose names are never called/when choosing sides for basketball.”

• Christian Laettner—misunderstood lug or legitimate cocky asshole?: Legitimate cocky asshole. He’d tell you as much himself, which was a big part of his success.

• One question you would ask Soulja Boy were he here right now?: “You any relation to Arn Tellem, the Detroit Pistons executive, former player agent, and erstwhile Cheltenham (Pa.) High School classmate of ex-SI staffer Franz Lidz?”

• Elena Delle Donne as a serviceable low-level Division I shooting guard … possible? Ridiculous? Both? Neither?: I adore her game, and I’d love to see what she’d do dropped in among guys—but if you want real serviceability, probably best to try her at D-II or III.

• What are the most overused words in the Alex Wolff writing catalogue?: Maybe it’s my German heritage, but I love words that result from two other words getting scrunched together. Words like gainsay and woodsmoke and hardscrabble. Love them too much, probably.

My wife is my first reader, and she’s genuinely surprised when I write something that doesn’t have hardscrabble in it. Or hard by, as in, “a cabin that sits hard by a silo.” That’s a lot of hard. Guess you could say I take Viagra for my vocabulary.

• How do you feel about Donald Trump as president? (being quite serious): (Cue the growls from the pit of my stomach.)