So a couple of months ago I was driving home from Los Angeles when I began to play the latest episode of Seth Davis’ regularly fantastic podcast.

That week’s guest was Dave Kindred, the former Washington Post columnist and a man I both admired (as a scribe) and knew little about (as a human). To be honest, I figured it’d be a bunch of stories about the good ol’ days from a writer who chronicled some of the biggest moments in sports over the past half century. Instead, much of the episode was devoted to, well … um … eh … a high school girls basketball team in tiny Morton, Illinois.

This, I thought, is unexpected.

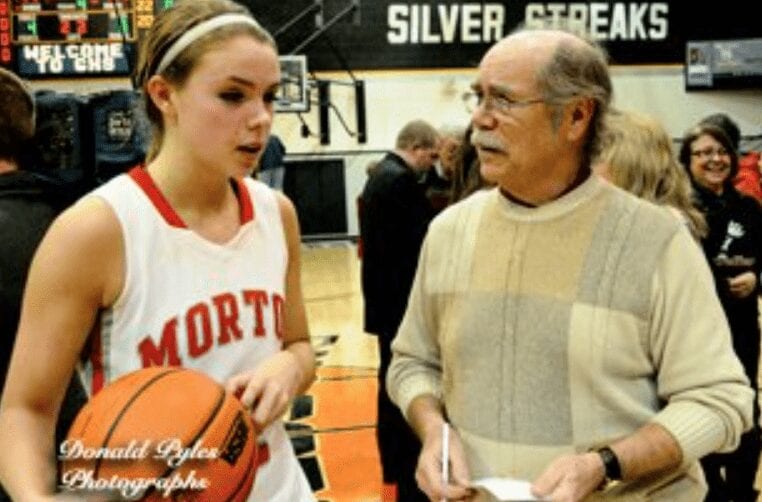

It turned more so. In his retirement from newspaper, Kindred has been covering girls prep hoops for … his Facebook page, as well as a local website. And here’s the beauty: He loves it. Like, loves loves loves it. Attends every game. Knows the girls and their parents. Has even written a pair of books about the Lady Potters. I was both mesmerized and dumbfounded, and decided, at that moment, the Quaz needed Dave Kindred.

So here he is. With stories of girls basketball, and Muhammad Ali, and Joe Theismann; with his take on the death of print and the thrill of capturing a moment.

One can follow Dave on Twitter here, and visit his Facebook page here.

Dave Kindred, you are the 298th Quaz …

JEFF PEARLMAN: So you’re The Man. Truly. A journalistic legend, an all-time great talent, someone I’ve admired for decades. And right now, as we speak, you’re covering—100 percent by choice—the Morton High School Lady Potters basketball team for a local website and on your Facebook page. Um … why? How? And does it bring you the same satisfaction, of, say, a World Series or big heavyweight fight?

DAVE KINDRED: To answer the easy question first: Yes, the satisfaction and the dismay are the same, all depending on how well I reported it and wrote it. It has been my blessing and curse that whatever I write, I try to make it better than the last thing I wrote—or at least the best thing I can write with the material at hand. The only real difference is the pay. Newspapers and magazines pay better than my Facebook page, though the Mortonladypotters.com website does pay with a box of Milk Duds occasionally … Morton, Illinois, is a small (pop. 16,670) west-central Illinois town next door to Peoria. After 45 years away, my wife, Cheryl, and I moved back in 2010. I went to a girls’ game because my sister had been a long-time babysitter for one of the players. I found out there was a team website. I asked the webmaster if I could write for him. He later said he sized me up as “some disheveled guy just coming out of the stands.” I told him, “You could Google me.”

I’m now in my seventh season. I’ve written over 200,000 words on the website and have done two books on the Lady Potters following back-to-back state-championship seasons. (You could order them from the website. Thanks.) Why do I do it? Why does anyone work for no pay? It feels good. It feels right. It’s where I started, in little gyms around Illinois. It’s a game I love, basketball, and the Lady Potters play it with class, elegance, and grace. They’re now on a three-year run during which they’ve won the two state championships and 78 of 84 games. John Wooden liked women’s basketball. He said women can’t overcome mistakes with physical strength, and they only rarely can create their own shot. So they must master the fundamentals of ball-handling, defense, rebounding. For the same reasons, Draymond Green has said he likes watching the WNBA.

Here’s a thing, too—it feeds my reporting addiction. I don’t go to Lady Potters’ games for the “experience,” the spectacle, the hype that big-time sports sells. There are no cheerleaders, no halftime extravaganzas, nothing but four eight-minute quarters and you’re done. I go to watch a game and find a story. Stories are everywhere, you just have to pay attention. That’s what I’ve always done, whether it’s a Super Bowl or a World Series or an Ali fight—I ignore the hype and write what I’ve seen, what I’ve learned. I mean, if I go to a Broadway show, I want to go backstage afterwards to ask the actors why, why, why. After a Lady Potters game, I wait around with the parents on the court—pure Americana, pure heartland—and wait for the players to show up. I ask them why, why, why. Then I go home to the typing machine and try to earn my Milk Duds.

J.P.: I’m gonna go totally random here, because it’s my Q&A and I can be as odd as I please. In 1987 you were the ghostwriter of Joe Theismann’s autobiography—the memorably titled, “Theismann.” I’ve never ghosted a book because A. You split the money; B. It seems pretty thankless. So what was the process like for you? Was it fantastic? Awful? Was Joe an interesting man? And how’s the book?

D.K.: In my time as a columnist at the Washington Post, Joe had been a reporter’s dream. He’d won a Super Bowl, he was counted as one of the game’s best quarterbacks, and he would talk all day on any subject. For all those reasons, I once proposed doing a book together. He passed on the idea—until Lawrence Taylor snapped his leg in two. From his hospital bed, Joe called me. “Dave, that book you wanted to do, I’ve got time now.” I wasn’t a “ghost” in that I was invisible. I’d call me an accomplice. My name was on the cover in small print, “With Dave Kindred.” But after “Theismann,” I never again aided and abetted in someone else’s literary crime. It was like studying to be an architect, then building a doghouse. Not to disparage Joe. He loved football and he was a quote machine. If you didn’t ask to interview him, he’d pick up your tape recorder and interview himself for you. My favorite moment in the book process came when I asked how, at Notre Dame, he passed for over 500 yards against Southern Cal during a game-long rainstorm. How could he throw so well in the rain? He loved to talk about that game, a signature moment in his career. I was interested in the craft of that moment. Really, Joe, how did you do it? He began an explanation that got around to different finger pressures on different places on the ball. But when he couldn’t really explain the explanation, he gave up. He said, “Aw, that’s just bullshit. I have no idea.”

The book was as good as I could make it. It had some good stuff on George Allen, Joe Gibbs, Jack Kent Cooke, and John Riggins. The book’s publisher also wrangled a memorable blurb from John Madden. It’s on the back cover. In its entirety, the blurb goes, “Hey, not bad!”

J.P.: You’ve written a ton on Muhammad Ali over the years, including a book, “Sound and Fury,” about his relationship with Howard Cosell. This might be a quirky way of approaching the subject, but … do we at all overstate or overrate Ali’s greatness and meaning? I’m not referring to his boxing skills. I mean more along the lines of his late-life status as a holy, near-Gandhi-like figure …

D.K.: Ali was whatever you wanted or needed him to be. A sweet-hearted saint? OK. A crueler-than-hell sinner? OK. That’s no answer to your question, but it’s the best answer to the mystery of a man once reviled and finally, in his years of brain-damaged silence, revered. He was a follower, not a leader; he was a symbol, not an actor. He gave us reason to despise him and he gave us reason to love him. It was up to each of us to decide what we wanted him to represent. If we think of him as a great man of principle—for refusing the draft, for being willing to go to prison for his beliefs—we should also know that he didn’t refuse the draft so much on principle—he had no idea what that war was about—as he refused on orders from the leader of a racist cult/religion, Elijah Muhammad. That said, it is yet true that his refusal inspired thousands, if not millions, of protestors against that war. They didn’t care if he couldn’t find Vietnam on the globe or had never heard of dominoes falling in Asia or simply didn’t like the idea of getting shot. They cared only that the most famous man on earth stood with them at risk of his career and life. Ali’s resistance against the most powerful government in the world was no small thing, however it came to be. He gave courage to lots of folks, black and white, in lots of ways.

J.P.: Your professional career was spent largely at newspapers. Now newspapers are, print-wise, on the verge of death. I’m wondering how this makes you feel, and if you believe the business did anything wrong, or whether it was merely inevitable?

D.K.: I’m a newspaperman and proud of it. I once dedicated a book to my grandmother, Lena, who every Sunday in Lincoln, Illinois, sent me to the train station to pick up the three Chicago papers. l grew up with the inky smudges of newsprint on my fingers. A newspaper paid my way through college. I won a journalism scholarship with an essay about why I’d like to be a reporter. All I remember about the essay is that I said I was curious. I wanted to know things. After college, newspapers paid my way through life. For 50 years going onto 60, I couldn’t imagine starting a day without reading two or three newspapers. For one thing, I thought it was a citizen’s duty. How else do we know the difference between a Trump and a Clinton? But now the media landscape is so broad, with so many vehicles, that I rarely touch newsprint. I read the best newspapers online, and Twitter has become my daily index to news I might otherwise miss. I’m a dinosaur trying to stay alive.

J.P.: You have a go-to line that has emerged as a favorite of mine: “If you pay attention, you’ll see something you’ve never seen before.” First, do you truly believe this, or is it more like, “An apple a day keeps the doctor away”—sorta kinda correct, but not fully? And, second, how had the approach and thought process impacted your career and your writing?

D.K.: The full line finishes … “and write about that.” Yes, absolutely, I believe it—not 90 percent of the time, not 95 percent, 100 percent of the time something will happen you’ve never seen before, you just have to have paid attention long enough at enough games to know what thing thing is. It doesn’t mean the thing has never happened, it’s just that you have never seen it before and now you have a chance to learn something and pass it along to readers with the enthusiasm that comes with discovery. Last season during a Monday Night game, Jon Gruden, who has seen more football than any of us, saw a punter make a helmet-to-helmet tackle and practically jumped out of the TV booth. “I’ve NEVER seen that before,” he said.

Some of the never-happened-before stuff is obvious. When Bob Knight throws a chair across the court, yeah, we’ve never seen that one. Some of it, you really have to be paying attention—and by “paying attention,” I don’t mean just watching closely, though that’s the foundation of it all. I also mean putting yourself in position to see things happen. One of the Lady Potters twisted an ankle badly the other night. The coach and an assistant CARRIED the girl, sedan-chair style, to the locker room; then her father CARRIED her, like the baby she once was, out of the locker room. I’d never seen that before. I wrote about it, I even took a picture of it. Here’s another one:

At Augusta three years ago, I told a buddy, Steve Hummer, “Let’s go out,” meaning out of the media building. (Red Smith’s advice to reporters: “Be there.”) Steve and I walked to a spot behind the second green. Louis Oosthuizen, from the top of a distant hill, hit a shot that flew forever, landed on the left side of the green, then turned toward the flagstick, rolling, rolling, the crowd’s noise rising as the ball rolled forever, always toward the hole—until it fell in. A double eagle. We started interviewing people. We hadn’t been waiting in the media building for news to be handed to us. We’d been paying attention and we saw news happen. We wrote about that.

J.P.: I’m of the belief that every longtime journalist has a money story. Meaning, you’re at a party, a bunch of people are gathered around—and you tell this gem. For me, it’s probably the whole John Rocker thing, which I’ve recited a solid, oh, 800 times. Dave, what’s your money story? The single weirdest or craziest or coolest thing to happen in your career?

D.K.: I once was in bed with Muhammad Ali. It’s the lead anecdote in my book, “Sound and Fury.” Amazon probably lets you read it for free. But one that I’ve not written? The night Bob Knight cuffed the Kentucky coach upside the head—then didn’t want to talk about it. It was December of 1974. Had it happened after ESPN’s creation, you’d have seen it on TV on a 24-hour loop. Knight’s first great team had Kentucky down by about 30 late. Suddenly, Knight is standing at mid-court with Kentucky’s Joe B. Hall. The game is flowing back and forth while the coaches are standing there. I see Knight drop his right hand behind Hall’s back. Then he brings it up swiftly, cuffing the back of Hall’s head, knocking him off balance. Knight drops the hand in front of Hall as if to shake hands. Hall refuses. Now we go to the press room after Indiana wins big. Maybe 30 reporters are there. People ask questions. I wait for the play-by-play reporters to ask their questions. I don’t care about the game. Finally, I raise my hand. I’ve known Knight a couple years by then. I know his combative, combustible personality, and I’m about to know it even better. “Coach,” I say, “what happened there with you and Joe?” Knight doesn’t answer. He looks around the room. “We’re here to talk about basketball. Anybody got a basketball question?” The dutiful press, sitting in little desk-arm chairs like 6th-graders, asks three or four basketball questions. I raise my hand again. “Coach, you and Coach Hall there at mid-court, what was going on?” Knight sees me, even hears me, but I am nothing he cares to acknowledge. “We’re here to talk about basketball,” he says. “Anybody got a basketball question?” Questions follow. Now I am more afraid, professionally, to not ask my question than I was to ask it in the first place.

Still, I ask some version of the question again, Knight ignores me again, until he turns those coal-black eyes my way and says, “Now, David, what did you want to know?” I say, “Coach, 17,000 people saw you hit the other team’s coach. What happened between you and Coach Hall?” At which point, Knight gives some non-answer answer about how cuffing someone on the back of the head is a sign of respect and admiration, something he does to his players all the time. Well, OK, yeah. I leave and return to my typewriter where I’m writing a column until I look up and see a bear lumbering across the basketball court. A bear. That’s what Knight looked like back in the day. Big, strong, no shoulders. I turn to my neighbor in the press row and say, “This can’t be good.” Knight climbs up to my row and sits beside me. Then he says, “How do I get myself into these things?” I begin breathing again. He seems a touch remorseful. He seems a touch human. I ask him some questions, now doing a virtual live column, just dropping in his answers. And we got along well for the next 40 years.

J.P.: How did you go about writing columns? I’m talking soup to nuts here. You have a column due in two days. It’s, oh, baseball season. You would do … what?

D.K.: Let’s say the subject is PEDs and Cooperstown. I know what I think of Cooperstown, that it should represent the best of the best, those players who dominated play in their time. I long have discounted the “character” clause because that’s laughable, considering the men already inducted. From that baseline, I read what smart people have said about PEDs. I read histories of the game. I make phone calls to sages. A day of such work and review suggests a premise for the column. Let’s say the premise becomes “Who cares? They all did it.” The work provides lots of details supporting my premise and one or two details in opposition. Then the fun begins. You find a tone. Snarky, wise, comic, incredulous, whatever. And you write.

J.P.: How did this happen for you? I mean, when did you know you wanted to write? Hell, when did you know you could write? And do you think these things (writing skills) are natural gifts, or things one can acquire via work and reading?

D.K.: I was 17 when I wrote an English class theme for Miss Clarice Swinford saying I wanted to be a sportswriter. That decision came shortly after my father, then 47, challenged me to a race to first base. He won. Perhaps, I thought, I’m not going to be a big league baseball player; maybe I could be a big league baseball writer. The first time I understood what writing is, I was 13. Our seventh grade teacher, Miss Prior, read Jack London stories to us. I liked the sound of the words. I suppose I had a natural aptitude for writing, but I know I had to learn how to do it. I knew nothing about grammar, for instance, until I took Latin my freshman year in high school; Latin taught me English grammar. I have never stopped trying to learn. I’ve worn out a dozen copies of Strunk and White’s “Elements of Style.” I read everything and I write all the time. I read good stuff, figure out why I like it, and then figure out how it can work for me.

J.P.: In a recent appearance on Seth Davis’ podcast you made it sound like you hated covering football and watching football. True? And why?

D.K.: I’ve written long enough to notice recurring themes in what I do. Boxing is cruel, so the columns feel like they’re soaked in blood. Baseball and golf are played on grass in the sun and under bright lights, so there’s poetry. Football, as George Carlin said, is war, it’s blitzes, it’s bombs. I prefer poetry to war, so I’d rather write golf than football. If we accept the truth revealed by autopsies—that football is a violent game killing brains—then how do we justify it as spectator sport? Armored gladiators in Rome announced, “We who are about to die salute you.” Is that what we want?

J.P.: Greatest moment of your career? Lowest?

D.K.: In the early ’70s, happy at the Louisville Courier-Journal, I told my wife we’d move only for the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times or the Washington Post. One day I walked into our kitchen and said, “The Washington Post called.” She said, “Oh, shit.” The day I sat in Ben Bradlee‘s office for a de facto “interview”—George Solomon did the hire—was, is, and will be the greatest moment of my career … The lowest? A day in June of 1991 when Frank Deford called to say The National was folding.

QUAZ EXPRESS WITH DAVE KINDRED:

• I’m sorta obsessed with this song lately. Thoughts?: I’m a musical illiterate. I liked the girl.

• Rank in order (favorite to least)—Gary Witts, black cherry soda, Peter Criss, toast with jam, Jim Fregosi, George Will, scented candles, the fourth night of Chanukah, Earl Cox, Michelle Obama, Gregory Hines, the alphabet: Alphabet, Earl Cox, Michelle Obama, fourth night of Chanukah, Gregory Hines, toast with jam, Jim Fregosi, George Will, Garry Witts, Peter Criss, (tie) black cherry soda and scented candles.

• Ten most talented sports journalists of your lifetime: How about I name a bunch who were/are fun to read, influenced me, and became friends? Red Smith, Jimmy Cannon, Bill Heinz, Bob Lipsyte, Dan Jenkins, Sally Jenkins, Blackie Sherrod, Jim Murray, Shirley Povich, Larry Merchant, Jerry Izenberg, Joan Ryan, Frank Deford, Dick Schaap, John Feinstein, Mark Kram, Peter Richmond, Hugh McIlvanney, Tom Callahan, John Schulian, Jane Leavy, Furman Bisher, Dave Anderson, Tom Boswell, Charlie Pierce. I could go on.

• Ever thought you were about to die in a plane crash? If so, what do you recall?: Chargin’ Charlie Glotzbach, a big-time stock car driver, had his own plane. I once flew with him to Indianapolis. As we descended to Eagle Creek airfield, a small plane appeared directly beneath us, apparently aiming to land in the same pasture. “Charlie?” I said. He did something that made us go straight up. The ascent also caused a buzzer to go off. A red light came on. Under the red light, the word “STALL.” I said, “Charlie?” He said, “We got 30 seconds.” So we went from going down to going straight up to leveling off and coming down again. Then came the really harrowing part: riding shotgun in a pickup to the race track at 75 miles per hour on blind-corner country roads. I never went anywhere with Charlie after that.

• One question you would ask Busta Rhymes were he here right now: Can you print out the lyrics for me?

• How did you meet your wife?: In high school. My sister made me date her. February 24, 2017, we’ll be married 55 years.

• Five greatest pure athletes you’ve ever witnessed live?: Ali, Michael Jordan, Griffey Jr., Carl Lewis, Secretariat.

• What are the three most overrated statistics in sports?: I want to waterboard the guy who invented WAR.

• You wrote for Sports on Earth. Why do you think it didn’t last?: I’m still trying to figure that out for The National.

• You have a brilliant mustache. What are the keys?: Stand in the shadows. That way it’s golden instead of white.