Weird few days last week.

ESPN laid off a shitload of people.

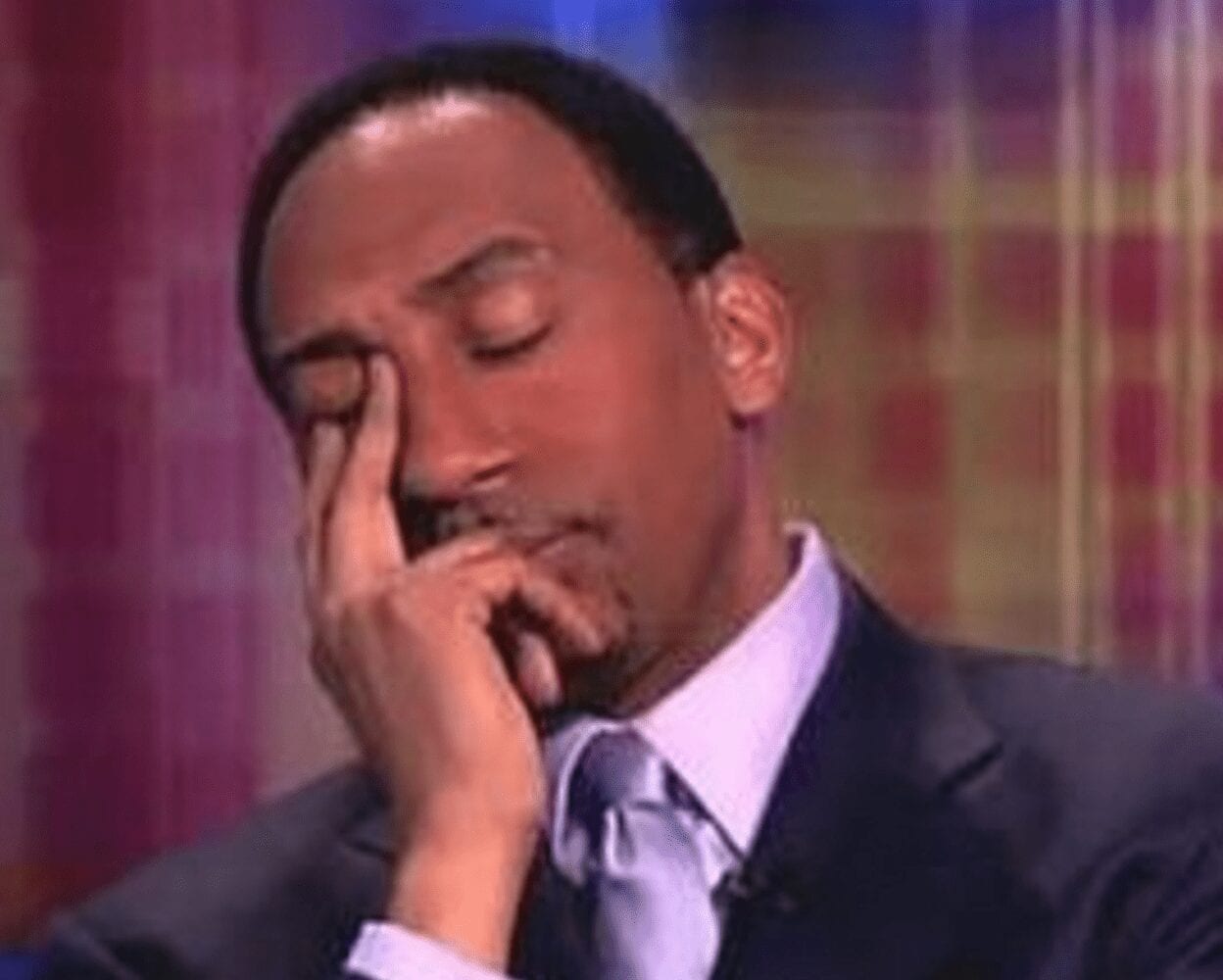

I wrote that it sucks how the network has lost interest in reporting and researching, but continues to pay enormous money to high-volume dolts like Stephen A. Smith.

That received a lot of reads and amens.

Stephen A. Smith didn’t care for my take.

He went on air and suggested (strongly) that race played into my criticism, saying—among other things—”Mr. Pearlman’s not black, maybe that’s why he doesn’t understand where I’m coming from” and “Like when they say to me, ‘Screamin’ A.’ — I’m the only dude on the air who’s loud? I know plenty of white dudes who are screaming and going off. They’re called passionate. I’m called loud.”

Of course, because research/detail isn’t really a priority with Stephen A., he failed to mention that:

A. I’ve never called him “Screaming’ A.”

B. On multiple occasions I’d levied the exact same charges (that yelling and arguing (for the sake of yelling and arguing) has replaced nuance and research) against Skip Bayless and Chris Berman and Mike Francesa. None of whom are, eh, African-American. This information could have been uncovered in a six-second Google search. But alas … why seek truth when you can charge a man (whose great crime is thinking you suck and symbolize everything wrong with modern sports media) with racism?

What followed was an avalanche of hate e-mails, hate Facebook messages and hate Tweets from people claiming I’m a racist, a fucking racist and a white man who only sees color. This is not a charge that’s easy to defend oneself against. In fact, it’s almost impossible—no matter the truth.

Which, to be blunt, is rough.

When I was a kid, my first heroes were my parents, and my second hero was Martin Luther King.

I was 10 or 11 when, as a school assignment, we were told to memorize and recite a speech. Other students in my 99-percent white school picked addresses from John F. Kennedy or Franklin Roosevelt or Ronald Reagan. I chose Dr. King’s Dream speech.

Why? I can’t even pick a single reason. The words hit me. The oratory skills blew me away. The message was so strong, so powerful. Before long I would be walking through my house, performing the speech aloud for anyone with a few minutes to listen. I vividly remember one Passover, when I was allowed to stand on my chair and perform for relatives. It was magical.

This does not mean I am not a racist.

During those same years, as a boy in Mahopac, N.Y., my best friend was an African-American kid named Jonathan Powell. The whole “we’re like brothers” thing has become a lame movie cliché for an unlikely bonding of two people, and it doesn’t actually work here, because we were not unlike. We both loved driveway hoops, Run-DMC, tackle football in the backyard. If I ever thought of Powell’s race (or he ever thought of my religion—Judaism), it was probably only when someone else made a comment. I vividly recall a neighbor asking why I like “niggers.” On those moments, I thought about it. Otherwise, no. We were just best friends.

This does not mean I am not a racist.

I joined the NAACP as a sophomore in college. I don’t recall why, save for being outraged by the ugliness that still impacted our nation, and that the group struck me as a righteous one.

This does not mean I am not a racist.

I was a young writer at The Tennessean in 1994, just starting my career, when I asked our film reviewer what he thought of Spike Lee’s new flick. He sort of snarled and said, “Just another nigger director.”

I was 22. The editor was in his 60s; a newspaper legend. I didn’t know what to do, so I wrote him an e-mail, saying how horrified I was; how Lee was one of my idols and—even were he not an idol—how could he speak of someone with such language?

This does not mean I am not a racist.

In 1999, I drove around Atlanta with a Braves pitcher named John Rocker. In our time together he ridiculed, mocked and attacked gays, foreigners, New Yorkers. He also called a black teammate “a fat monkey.” I quoted him at will, then was slaughtered afterward for “taking advantage.” I explained that I owed a racist no protection.

This does not mean I am not racist.

Many of my closest friends are African-American—this does not mean I am not racist.

In college my major was History, with a selected emphasis on the Civil Rights Era—this does not mean I am not racist.

I have been a journalist for 23 years, and before last week had never been accused of anything even approximating racism—this does not mean I am not a racist.

The truth is, nothing I write here means I am or am not a racist. Racism isn’t something you simply disprove with a sign, or past actions, or measured words. Honestly, I don’t know how one disproves racism once someone like Stephen A. Smith (or anyone, for that matter) drops the insinuation, as he did last week.

That’s what was on my mind three days ago, as I FaceTimed my nephew to check in. Jordan is 16 and I have been in his life since his birth. He and his brother Isaiah are two of the gems of my existence; kids I would do anything for. Jordan happens to be both bi-racial and attuned to sports media, and I figured he had listened to Smith’s diatribe. So as we commenced with casual chit-chat, I kept waiting … waiting …

“So,” he said, “I heard what Stephen A. Smith said …”

“Yeah,” I replied. “He sort of accused me of being racist. I was worried what you’d think.”

It would not be an exaggeration to say tears collected in the corners of my eyes.

“Uncle Jeffie,” he said, “I know you better than Stephen A. Smith.”