Blind Melon should have gone down as one of the greatest rock bands of all time.

I know. Blind Melon? The Bee girl? No Rain—the song people either seem to love or hate? Well, yeah. Blind Melon. The Bee girl. No Rain—the song I love, even though I’ve heard it 8,000 times. This is one of those things you’ll either have to trust me on, or simply learn for yourself by pulling out one of the group’s three albums. Because back in the early-to-mid 1990s, before singer Shannon Hoon’s death of a cocaine overdose, Blind Melon was putting out some of the most inventive, unconventional stuff in existence. People try to categorize the group as hippie rock, or alternative rock, or jam band, but none really sticks. They’re funky, cool rock—with a distinctive sound and vibe.

Anyhow, I’m babbling, because I friggin’ love Blind Melon. With Hoon’s 1995 passing, Blind Melon as we knew it passed, too. I mean, the band came back strong a decade ago with a new lead singer (Travis Warren—Quaz alum) and a solid CD (For My Friends), but Hoon’s absence changed everything. It just did.

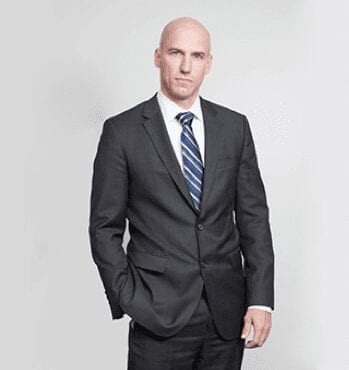

I digress. Today’s 231st Quaz Q&A is Rogers Stevens, the longtime Blind Melon guitarist who, last year, garnered some unique attention for graduating the University of Pennsylvania’s law school (in his 40s) and landing a job at Ballard Spahr as a labor and employment attorney. The band still tours, but only when the law will allow.

Rogers Stevens, dreams come true. You are this week’s Quaz …

JEFF PEARLMAN: Rogers, I’m gonna start with a weird question, and I hope it doesn’t sound inane. So, I think it’s cool that you went back to college, then law school, then got a job with a firm. I really do. But there’s also a small part of me that finds it, oddly, dispiriting. Like, to me you’re the Blind Melon Guitarist. You’re a tour bus to Oakland; you’re riffs between Shannon Hoon vocals; you’re Woodstock ’94 and SNL and all that stuff. Really, it feels a little like Peter Pan growing up, or Christopher Robin no longer believing in Pooh. Um … do you feel this way at all? Like, was there any conflict going from a life of music to a life of law? And does my question even make sense?

ROGERS STEVENS: Your question makes sense in a rambling sort of way. I think you could’ve focused it a bit more, maybe pared down the premises a bit. The question comes off like you were still working it out in your head while you were asking it. But I won’t hold any of that against you, and I find it encouraging that your brain is actually working for this interview, despite my low-wattage, faux-celebrity standing. Ultimately, I appreciate that you care—or that you do a fine job pretending that you care. Anyway, yes … I do understand what you mean. But I never saw it like that. I always make an effort to follow my instincts and interests. I have a fetish for challenging myself. I crave new experiences, and I’m not comfortable when I’m comfortable. Does that make any sense?

J.P.: I’m sure, in the 20 years since he died, you’ve tired of Shannon Hoon questions. But here’s a Shannon Hoon question: Who was he? What I mean is, I know he sang, I know he had drug problems, I know he died young. But … what was he like? Was he happy? Brooding? Friendly? Standoffish? Was he great, in the way some people have greatness about them? Or just a guy? And how often does he enter your mind at this point of your life, if ever?

R.S.: I’ll say this—he was all of “happy, brooding, friendly, standoffish” and much more. I’ve met a lot of people along the way, and he was clearly one of the most interesting and conflicted people I’ve ever met. First impression for most people was “star.” He was incredibly gregarious when he wanted to be. He pretty much talked all the time unless he was pissed about something. He had absolutely no capability of editing the content of what poured out of his mouth. The trick to Shannon’s brilliance was that he said everything, and about 5-to-10 percent of it was really cool. Of the remainder, a good portion of it was nonsensical stoner logic, which also had its moments. You would find yourself saying, “Yeah … that makes sense in an alternate universe.”

And that temper … wow. He was prone to volcanic rages that came out of nowhere if he perceived a slight, either to himself or those close to him. When he opened that door, you could see a very, very deep level of anger in him that was truly frightening unless you were used to it—I got used to it right away. I saw him fight too many times to count, and I never saw him lose. He actually loved it, or at least had no fear of it. He was not a big guy, but he was agile and strong, and like many good street fighters he had heavy hands. To clarify, though, he was not a bully, and he generally fought people who were bigger than him for some reason … I can think of several instances with police. He just did not like authority.

He did not trust journalists, although he befriended many of them. Had you asked him a question that gave him the impression that you were fucking with him, he would’ve had it out with you.

J.P.: On your Wikipedia page—and in your bio—there’s a sentence that says, “In 1988, Rogers and [bandmate Brad] Smith left Mississippi for Los Angeles to pursue their musical interests.” It’s an easy one to read over, but sort of fascinating. You were 18. What does it entail, being that young and picking up and moving? Did you drive? Fly? Where’d you stay? How’d you know where to go? Look? Be?

R.S.: Brad and I packed everything we owned into an early 80s Honda hatchback … a couple of guitars, sleeping bags, clothes, music. Honestly, we were completely nuts. Looking back on it, I understand now the risks. We were blessed with complete ignorance of what we were doing, and we just assumed that it would work. We were pretty matter of fact about the “dream.” We had been plotting it for a couple of years, not telling our families and whatnot, which in both our cases were somewhat fragmented. We had each other, and that was something that came to be very important once we got there. We didn’t know anyone, nobody would rent us a place to live, we ran out of money pretty quickly … I had to talk Brad out of standing on a corner on Santa Monica. We were in dire straits for a while. Neither of us had ever spent much time at all in a city, and I don’t think I had even been on an airplane at that point. I remember when we arrived in Los Angeles … we drove straight past it on the 101—out of the Valley toward Santa Barbara. We kept waiting for it to look like we imagined it, and it just didn’t from the freeway. I remember it was late in the afternoon by the time we turned back around toward Hollywood. We did not have a lot of cassettes in the car, but I remember REM’s “Document,” the Rolling Stones’ “Hot Rocks,” the Doobie Brothers’ “Greatest Hits,” AC/DC’s “Dirty Deeds,” GnR’s “Appetite” and some lame folk shit that Brad enjoyed but I hated. One of the first things we did that evening was go to Tower Records on Sunset. We bought Jane’s Addiction’s “Nothing’s Shocking,” because I had seen an article about it in Rolling Stone, and we were completely floored.

J.P.: I’m 43, and in the process of getting my masters degree. And I hate it. Like, r-e-a-l-l-y hate it. I feel like attending college has sorta passed me by. But you went back for both an undergrad degree, then a law degree. Why? What was the inspiration? And was it hard getting back into education? To thinking again as a student?

R.S.: I always read a lot of philosophy books—much of which I did not understand. But I made myself think. So when I went for that gear, it was still there. However, “getting back into education” would require having been into it in the first place, which I did not do. Once I got into the guitar, I was just obsessed. I missed the maximum number of days possible from grades 10-thru-12, skipping out to engage in my true studies. I’ll say this, though—it’s certainly not too late to do this if you’ve got a lick of sense. It just requires being interested and focused. Had I gone to college on a more conventional path, it would’ve been a disaster. I had to get my ya ya’s out, or at least enough of them so that I can concentrate. Still have a ya here and there … in fact, a lot of them. Always.

J.P.: As I mentioned, you played Woodstock ’94. I remember being a young newspaper writer, wondering, “Is this a great event or corporate nonsense? Is this cool or contrived?” You were there. What do you remember? And what was it?

R.S.: It was better in hindsight than in the moment. I had grown tired of being around crowds all the time—I think we all did. It was logistically difficult as well. A blur. I remember this: Airplane from Hawaii to New York, van from New York City airport to upstate near the festival, hotel for a few hours, van to somewhere else near the venue, another van, a helicopter (very cool) over the crowd, land backstage (really far from the stage), another van to a trailer, wait, then play. We were suffering the lingering effects of some substance procured from Porno for Pyros in Hawaii, and so many of us couldn’t get the snarl off our faces. The band was not great that day … it just didn’t click, but Shannon was amazing. We were doing a bunch of stupid stuff with our show at that time … refusing to deliver what we were capable of, simply because we had to make it “different” every single time. We could’ve delivered the goods and met Shannon on his level, but we just weren’t in the right headspace … frustrating.

J.P.: I love Blind Melon. I really do. But I wonder—and this might sound weird—do you love Blind Melon? Like, would you say you guys are amazing? Great? So-so? Do you think, had Shannon lived, you guys go on toe legendary things? Or do you peter out, like so many other bands?

R.S.: Sorta like asking me if I love my left leg. It’s difficult to be objective about my left leg, or the other one for that matter. I will go to my grave knowing that we would’ve really been great. We were in a period of rapid development when Shannon died. When we wrote/recorded the first record, I had been playing guitar only for a few years. It was still very difficult for me to play—perhaps it sounds that way. By the second record, we had developed a lot, and there were just too many ideas. We couldn’t address everything that everyone was doing. Much of it was good. I have a ton of outtakes songs that were coming together and I think they were potentially amazing. We would’ve forgotten all those had we gotten to the writing process for a third record. It was just happening really fast, and everyone had gotten so much better. I contend that nobody sounded exactly like us, and we would not be an easy band to cover. It was just crazy … nobody would play “normal” stuff. Everybody was driven to make it unique, and everyone had very high standards for what was acceptable. Fairly competitive within the band, and everybody wanted to shine. Much of it was a product of immaturity and substance abuse, but there were moments when it would stop you in your tracks. We were getting to the point where we could’ve tied those moments together. For us at least, it was just crushing to stop where we did … I’ll never get over it.

J.P.: Greatest moment of your musical career? Lowest?

R.S.: Greatest moment was the very first note I heard out of Shannon’s mouth. That’s when I knew we would do something. When Brad and I arrived in Los Angeles, we had plain ol’ dumb optimism, and for no good reason. However, after looking around for a while, and trying to work with some other singers, we came to realize it was going to be difficult, and perhaps that the odds were against us. But then Shannon opened his mouth, and it was incredibly musical in a way that was perfect for the style we had developed along the way. Christopher and Glen joined us and it was complete. It was perfect, or at least we knew it would be.

Lowest moment? Hmm … we had a couple of failed recording sessions that were frustrating. Hard to think of any performance as a low moment … when people watch and listen, you’re an asshole if you don’t appreciate that. I’ve had plenty of shows where I played poorly, but I can’t say I would’ve rather not played any of them.

J.P.: Why do you think bands with members in their late 30s, early 40s can’t score on the regular pop charts? What I mean is, even had “For My Friends” been the second coming of, say, Abby Road, there’s no way it would have been a staple on pop radio, because kids wouldn’t have responded. But … why? Isn’t good music good music?

R.S.: It’s always been a youth-driven biz, and rightfully so. Young people will always be an endless source of new ideas, and most of them do not want to hear from “old” people. And “old” people aren’t as invested in it once they have families and mortgages. It just doesn’t seem all that complicated to me. I submit that rock music, or pop music, is best made by and for young people. Abby Road was made by some 20-year olds. There’s a certain amount of room for “adult” artists, but those records need to be very well rendered to break out of that limited market. I like about half of “For My Friends,” and think it could’ve been better had we not been going through our usual difficulties … I know a lot of bands are internally unstable, but this one is exponentially more so than most.

J.P.: I know it’s been a long time, but … your lead singer dies. You’re still a very young guy. It happens—Bam. What are you thinking? Like, you find out, you digest the news. Are you like, “OK, new singer”? Or are you, “Shit, we’re fucked”? Or are you simply overcome by grief?

R.S.: Chaos. What to do? The first-order problem was the death of my true friend. A few hours later you’re supposed to be onstage, and people start asking whether you’ll go to the venue and say something …

We just didn’t have any way to deal with it. We were already winging it on the road, as always, and then we had to figure out what to do. The worst was getting on a plane and flying back to Seattle and then sitting in my house by myself. It took me about 15 minutes to figure out that I had to leave. I was on the road with all my stuff driving to New York City within three days. We thought about a new singer, and even looked around, but we were just clueless and didn’t know what else to do. We should’ve known that the star of the band was gone and we were over … but it was sort of like waking up and discovering the laws of physics were no longer in effect. What would you do? It took us many years to even be available to the idea that we could keep going. And Travis came along and was really great, so that got us going.

J.P.: I’m gonna throw a random one at you: A few weeks ago the wife and I went to see Hall and Oates. It was a huge outdoor amphitheater, sold out—and they played a 50-minute set. I thought it was pretty bullshit, and I LOVE Hall and Oates. What says you? Is there a minimal amount one must play? Does it matter how many hits you have, or how old you are?

R.S.: We’re pretty conscientious about giving people their money’s worth. I don’t know many performers who aren’t. And stuff happens. Maybe Daryl gave John an unusually aggressive wedgie before the show and it set John off … no matter how hard you try, sometimes people don’t get their money’s worth. That sucks, but it happens. We’ve cancelled so many shows, tours, appearances, etc. I always feel terrible, because I know how I would feel in that situation.

QUAZ EXPRESS WITH ROGERS STEVENS:

• Five greatest guitarists of your lifetime?: Keef, EVH, Jack White, Clapton!—and I’m leaving an open slot for all the ones I love but will not remember right now.

• Rank in order (favorite to least): Anna Kendrick, Travis Warren, Bartolo Colon, Milwaukee, John Carlos, Willie Gault, Johnny Manziel, long walks on the beach, People Magazine, egg sandwiches, wood tables, “Gin and Juice”: Kinda fucked up to throw Travis in there, because I now have to put him first or otherwise listen to him bitch and moan. I can’t help it … I want Johnny Manziel to do well because I love a fuckup who can still manage to excel. I’m writing this on a wood table, so that’s something I enjoy. Milwaukee is difficult, but I am open to exploring it with someone who really knows it. I like to walk on the beach for about 15-to-20 minutes, but then get freaked out because I think I’m being lazy—I realize that’s somewhat lame. “Gin and Juice” is familiar … I know the track … we were so busy at the time that I didn’t give it the attention it warrants. For the rest, I’m familiar with the sports people, but don’t know who Anna Kendrick is. I’m sure she’s fabulous. Love an egg sandwich on occasion.

• My kids think Christmas in Hollis is the greatest hip-hop song of all time. Which is sorta odd, because they’re Jewish. Thoughts?: My kids are a coupla half-breeds, so I’m familiar with the challenges of Christmas. We go down to Mississippi and they love Christmas, etc., of course because of Santa. I think the Jews need a Santa-like gimmick to really put things over the top. I know there have been efforts, but it’s tough to compete with the presents. I spent some time in Israel, and it’s the most extraordinary place I’ve ever been. I just realized that I’ve never heard “Christmas in Hollis.”

• Ever thought you were about to die in a plane crash? What do you recall?: Yes. My wife and I were flying into San Paulo in the dark. There was turbulence. Or just one turbulent moment. It felt like God had punched the nose of the plane. People hit the roof, and I looked over at my wife … she was so whacked out on Xanax (a necessity for her) that the drool sort of sloshed off her lower lip. She looked at me and asked me if we were in Rio yet. I told her to go to sleep and I’d see her on the other side hopefully …

• I fear death—the inevitability of nothingness. Does it plague you at all? If no, why?: Best question ever. I live with a constant sense of existential dread that is neither interesting nor novel. I am one of those who will never find inner peace. I’m just going to squirm around for a few more years and then die. And I have no expectations for anything beyond that. I’m not ruling it out, but there’s just no way to know. I do know this—atheism and any sort of religious belief or other belief of the afterlife or of meaning to any of this … these are all equally illogical positions. And “meaning” is whatever you can manufacture while you’re here. Like Santa …

• Five reasons one should make West Point, Mississippi his next vacation destination: 1. People—Southern hospitality is a very real thing. I took my commie Jewish in-laws down there, and they were shocked. They loved it. 2. The South gets a bad rap, and much of that is legitimate, but if you went to West Point, you’d be in Howlin’ Wolf’s hometown, a short drive from the origins of William Faulkner and Tennessee Williams, Elvis, etc … just go down the list. A good portion of what I consider to be great American culture comes from right there—but it’ll take you a while to get a sense of it. 3. Unlike anywhere else in the world, I feel completely comfortable there … the pace of life makes sense to me, even though I’ve lived in cities since I left at age 18. 4. The music all makes perfect sense to me because it reflects that pace. I can play any of it because it’s just in me.

• Would you rather receive a check for $1 million in the mail, or never have to go to the bathroom again?: I place a premium on bathroom time … highly valued in a house with two grade-schoolers. Tough to put a price on it. Hmm … I’ll get back to you on this one.

• Who wins in the third Rocky Balboa-Clubber Lang fight?: Nobody wins that fight. Or they both do. At this point, I’m guessing they would both benefit from the pay-per-view.